Severe blow kills girl almost instantly

The stretch of highway off Church Street that we nowadays call Manchester Road was a densely populated area in the 1850s with terraced homes, several public houses and even a cotton mill.

At that time the highway consisted of three sections namely Water Street, Leeming Street and King Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmong the residents of Leeming Street were the family of tailor Owen McCulloch, who would be thrust into the spotlight following a tragic event on the second Saturday of September, 1854.

That evening Owen McCulloch, aged 42, returned home at about 11 o’clock having been drinking in the nearby inns.

His daughter Mary, aged 10, was sat on a stool by the fireside, nursing the family’s infant child and when McCulloch entered the parlour he enquired if anyone had fed their pet ferret. His son replied from upstairs that he had not, the daughter then remarking that a man had been to the house and taken the ferret away.

McCulloch, on hearing this, became much excited, and went towards his daughter to slap her for allowing the ferret to be taken away.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust at the moment, however, McCulloch’s wife entered the house, and seeing her husband with hand uplifted, as though about to strike their daughter, went towards the daughter and was struck a violent blow to the face by her husband.

Floored and dazed by the blow she did not observe what followed, but it was suggested that McCulloch then struck the daughter a severe blow to the head, either with his clenched fist or with a stick. She and the stool upon which she sat fell over, and she died almost instantly.

At least this was the version of events that was told on the following Monday afternoon at the inquest, held in the Town Hall, into the sudden death of Mary McCulloch.

The hearing heard that the death was only reported the following day when a doctor was requested to attend the house, by which time McCulloch had left home. He had remained in hiding until the Monday morning when he surrendered himself to the police. Being taken before the magistrates a couple of hours later to be remanded in custody until the inquest verdict was known.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMcCulloch attended the inquest besides his solicitor Mr. W. Blackhurst. The tale of the ferret and the ensuing commotion was told by Mrs. McCulloch.

A neighbour, John Butterfield, a brother of Mrs. McCulloch, told how he had been called around midnight and saw McCulloch cradling the dead girl and was clearly in a traumatised state.

He stated that both the parents had claimed it was a complete accident. A doctor called to give evidence stated that in his opinion the injuries from which the girl died could not have simply resulted from a fall. The coroner, Miles Myres, addressed the jury and asked them to consider whether or not the child died from any blow or from the fall, or indeed if McCulloch had a lawful right to attempt to strike her causing her to fall.

The jury then retired for consultation and they returned within ten minutes with a verdict of ‘manslaughter against Owen McCulloch’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

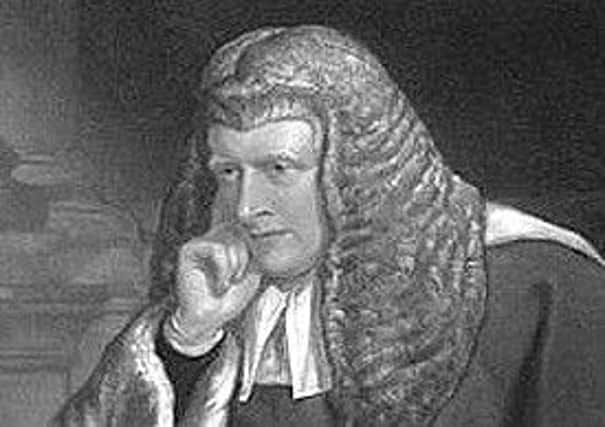

Hide AdIn mid-December 1854 the accused appeared at the Liverpool Winter Assizes before Mr. Justice Erle on a calendar that contained no less than twenty-three charges of manslaughter.

The prosecution told the court that Mrs. McCulloch was present when the incident took place; but that they were unable to call her, as she could not give evidence against her husband in a case of this kind.

As various witnesses were called it was apparent that the prisoner was clearly distraught over what had occurred and had been cursing and swearing and had expressed a wish that he was dead also. The jury after a lengthy consultation returned a verdict of guilty of manslaughter, but recommended mercy for him. Mr Justice Erle after considering the plea declared that Owen McCulloch would be imprisoned for two calendar months – a sentence that seemed to please the family members in the crowded court room.