When the plague swept through Lancashire

We know that Preston did not escape the awful consequences of the Plague or Black Death that ravaged the whole country over a long period, especially in the 16th and 17th century.

There is documentary evidence that Preston was visited by the Plague, the greatest calamity ever to hit our island, in 1349-50, 1466 and 1630-31.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the middle of the 14th century, the county suffered very severely from the effects of this pestilence, with it recorded that within the Hundred of Amounderness more than 13,000 people are said to have died from it between September 1349 and January 1350.

The two towns which lost the greater number were Kirkham and Preston, in each of which 3,000 folk are reported to have died.

Poverty was certainly prevalent at the time with records showing that only about 500 of the Preston victims had an estate of £5 or more, and of those only 300 had made a will.

The roll call of the dead included William Mirreson and his wife, Thomas Marshall and his wife, Robert Litester, John Tilleson and William Wrotchol.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRecords also show that, towards the close of the year 1349, the Chapel of the hospital of Mary Magdalen was closed, and so remained for eight weeks in consequence of the ravages made by the Black Death.

And we do have detailed information on the latter visitation that can be found in the registers of the Parish Church. Commencing with the year 1630, it contains the following significant entry: ‘Here beginneth the visitation of Almighty God, the Plague.’

Nothing more than this bold statement; the rest of the terrible story is told by the rapidly increasing number of burials as the dreadful months passed by.

In November there were 10 burials, and then those pathetic happenings continued to increase in number, until July of the following year, when the number reaches the appalling total of 321, while in the previous year there were only three burials in July.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThree hundred and twenty-one is a frightful record for one month. For the calendar year 1631 the total recorded funerals were 951 – a frightening statistic even though the Parish Church was the only burial ground in the town.

Husbands and wives, parents and children, masters and servants, were victims and often buried on the same day, or rapidly following each other to the grave. In some cases whole families seem to have been contaminated; no less than one-third of the population was affected in the 12 months that the epidemic lasted.

Not a single marriage was solemnised during the same period as fear and uncertainty reigned. The trauma recorded in the Parish Church register is confirmed in the Guild Order Book of the period with the following entry:

The great sickness of the Plague and Pestilence wherein the number of eleven hundred persons and upwards dyed within the town and parish of Preston, began about the tenth day of November 1630, and continued the space of one whole year next after.

Signed William Preston, Mayor of Preston.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne familiar figure of those plague infested days in Preston was William Lemon, who was the Mayor of Preston in 1624 and 1633.

He was the owner of the Alms Houses in St John’s Wynd called Lemon’s Alms Houses, and it is recorded that his father was a victim of the plague and was buried in late August 1631.

Fortunately, normality returned in 1632, with just 39 burials recorded.

The Black Death was mainly a rat-borne disease, transmitted from rat to rat, and from rat to man, by the bite of rat fleas. It was the day of the black rat, rife in the wooden framework buildings filled in with clay and plaster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Plague was one of the most infectious and deadly diseases of those early days and many methods were adopted to keep towns free from infection. People fled from infected districts hoping to find some place free from the scourge, but they often carried the germs and fleas with them.

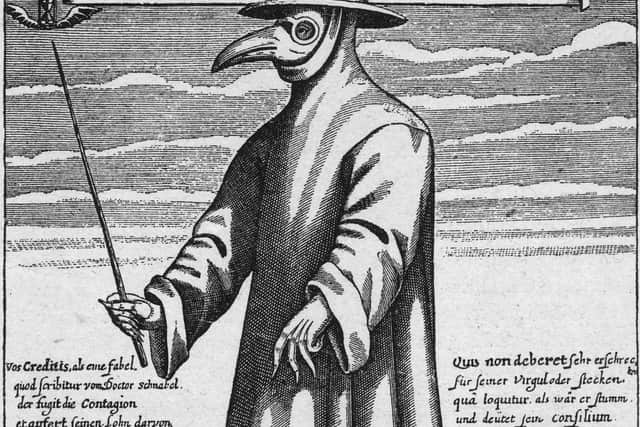

Town authorities took precautions against entry and the regulations were harsh. Citizens were forbidden to visits the markets and fairs of infected towns. Doctors wore protective clothing including a beak mask which held spices thought to purify air and a wand to avoid touching patients.

London was recognised as the chief source of the infection and even the first Parliament of Charles I reign at Westminster was adjourned to Oxford, because the Plague was raging in the capital.

Among other causes, foul air from moors and fens, standing water and sewage, and multitudes of people living in small dwellings uncleanly kept, were blamed for the terrible epidemics.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor the purification of houses, or personal preventive, vinegar was regarded as the sovereign remedy.

According to the physicians of the day: ‘They who are infected are cold without, hot within, are heavy, weary and lumpish; have great pain in the head, sadness of mind, sleepiness, loss of appetite, thirst, vomiting, dryness of the mouth.’

The preventions they recommended included leaves of carduss, butterbur roots, rhinoceros blood and hide boiled in sorrel water.