Dangers beneath Lancashire's fields

The outbreak of war in August 1914 affected the operations of Lancashire’s salt mines as many men either volunteered or were called up for military service. Not all of them returned and their jobs were increasingly performed by women both above and below ground.

Much of the work was manual, varying from store work to loading trucks with rock salt, using picks and shovels, digging trenches for pipelines and so on, but the women performed their work with skill and good humour and productivity does not seem to have been affected by the war. Operations were intended to continue as normal after the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, further troubles began in March 1919 when brine was seen to be dripping from the roof of the top mine, a worrying portent since water in a salt mine is extremely dangerous. The problem escalated and within a year between 7,000 and 8,000 gallons per hour were pouring through the roof, originating in No. 2 shaft and entering the mine via No.5 shaft and a tunnel, all of which had to be filled in.

In June 1923 a 12 foot deep hole suddenly appeared adjacent to No. 54, which was being dismantled, as the Fleetwood Chronicle reported, and within a week it had expanded to the shape of “a wine glass, with a rim of 35 yards in diameter and about 60ft deep, the stem being formed of a circular shaft about 15ft round running to a depth not known but probably extending to the brine cavity.”

By August 10 parts of Acre Lane had become unsafe, some farm buildings had been demolished, and the crater was 60 yards in diameter and 60ft deep. On September 28 the Chronicle reported, “the huge subsidence which is causing so much interest in the Over Wyre district shows no sign of ceasing.’’

The diameter was now 120 yards, converging on a small hole 75ft down, beneath which was a cavity up to 400ft deep into which hundreds of tons of earth, the greater part of an orchard and several farm buildings had all disappeared.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn October 5 under the heading , “The cavity that roars’’ the Chronicle further reported. “there come sounds as of the rushing of a subterranean cataract, then a rumble rising to the roar of thunder. The roar has been heard at Pilling four miles away. This great hole, which is visited daily by hundreds of people from near and far, including many geologists, is of such a depth that it could swallow the Blackpool Tower and leave no trace of it.’’

Alarming events were again reported on January 18, 1924 when. “many persons were awakened in the small hours of Sunday morning by bedsteads quivering beneath them. Far from any signs of becoming filled up, the hole seems to be getting bigger and people who had previously thought that the subsidence held no terrors for their own property are now discussing the question of how far it will eventually extend.

“At night, brilliantly illuminated by huge white and red arc lamps, the scene of the subsidence is an eerie spectacle. Coloured lights make the shiny sides crimson in appearance and the terrifying sounds of titanic earth combats which ascend from indeterminable depths make even the most hardy step back hurriedly.”

This latest subsidence, known locally as ‘Bottomless,’ eventually stabilised. Westfield Farm was demolished, Acres Lane was diverted, and operations continued, virtually as before.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

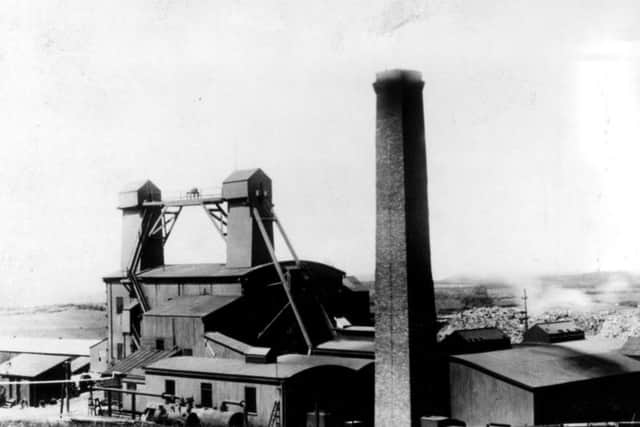

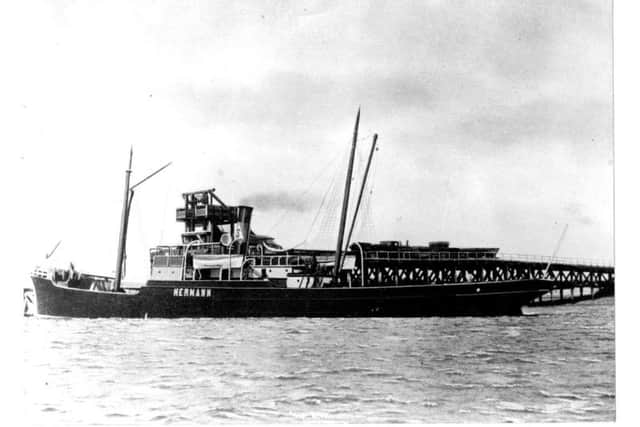

Hide AdIn 1926 the United Alkali Company became part of ICI and the emphasis in exporting rock salt changed somewhat from rail to shipping out from the nearby company owned Preesall jetty, but mining and brine pumping continued unabated until the next disaster struck. In June 1930 an area of land about 40 yards square at the ‘Flash’ subsided and water suddenly poured into the upper mine 450ft below with, “a roar which reverberated through the subterranean caverns’’ and all the men working on that level had to be evacuated, although work continued on the lower level.

Clods Carr Lane, the only access to Cote Walls Farm, had subsided and a new road had to be constructed. Blindly optimistic as ever, the Fleetwood Chronicle reported that all fears of further danger had been dispelled, the water had settled in disused workings and was to be converted into brine, and no further collapses had occurred or were expected.

However, the truth was very different. Salt is deliquescent and will dissolve itself even in damp air, so the ingress of water was a killer blow to the mine. Pumps were installed to pump out the brine but the 20 yard square pillars of salt supporting the roof began to dissolve and as a consequence the mine had to be closed early in 1931. All machinery was removed and the mine was completely flooded within a few months.

The Preesall operation was reduced to brine pumping only and the labour force of more than 300 men was reduced to only the 20 - 30 required to operate and maintain the brine wells and pumping machinery. Brine continued to be pumped out of the flooded mine until in 1934 the land above the mine, north east of the shafts, collapsed to form yet another lake known locally as the ‘Big Hole’ and pushed brine up the two mine shafts high into the air to flood the surrounding fields.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSince that time there have been only a few minor subsidences over the early brine wells, the pumping of brine from wells continued and even more were put down. In 1956 ICI purchased 20 farms amounting to 1,550 acres of land in Pilling from the Elletson family in order to secure their water supplies for future production, although some were later sold to the tenants. By that time all the buildings at the minehead had long been demolished and the jetty and rail links dismantled.

The site was left derelict, the two mine shafts being roughly boarded over, insecurely enough to allow teenage boys to drop lumps of brick through the gaps and wonder at the abyss beneath their feet. Brine pumping continued without any noteworthy disasters for many years, through the 1980s, until eventually ICI itself was dismembered and asset stripped, its large landholdings being sold off, enabling the Elletson family to purchase some land in Preesall to add back to the Parrox estate. Maintenance of the brine wells continued, the cavities being filled with a saturated brine solution and closely monitored. Now a successor company has purchased large areas of the ICI landholding and proposes, with government approval, to store huge amounts of gas in enormous new caverns.

And what of 17-year-old Dorothy Parkinson, the landlord’s daughter who boiled the very first sample of Preesall salt in 1872? She married another John Parkinson and spent her life as a farmer’s wife at Hackensall Hall Farm, rearing seven sons and two daughters, eventually dying in 1925, just a few years before the final act in the drama of the salt mine at whose birth she assisted. She played her part in our history and her descendants still populate Preesall and Over Wyre to this day.

I am one of them.

* With thanks to Rosemary Hogarth for permission to use her very extensive and detailed work on the Preesall salt industry without which this account would not have been possible.