Bloody battle left dead strewn across Preston

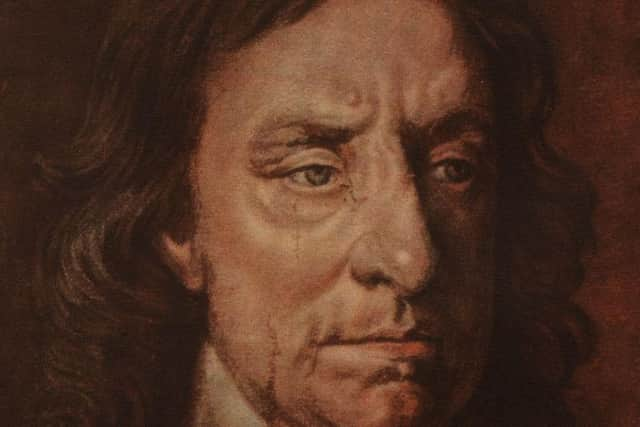

The Battle of Preston of 1648 deserves to be better remembered as a turning point in the execution of King Charles I.

The execution of the King in 1649 is one of the best known events in British history, and is very much associated with London, the House of Commons and Westminster Hall-but is was the

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBattle of Preston in August 1648 which paved the way for this hugely significant action by Cromwell and his supporters.

If the result of the fighting had been different, modern day Britain would be ruled in a totally different way.

Other civil war battles in the Yorkshire and South may be more well known, but they did not end the civil war between the forces of Charles I and Oliver Cromwell; that happened at

Preston, when over two days in August 1648, the last army loyal to the King was destroyed and humiliated. The more famous battles of Marston Moor and Naseby were not as decisive as Preston; they did led to the King’s defeat in 1646, but in 1648 he started the war again, this time with the help of a Scottish army which had supported parliament the first time around.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the summer of 1648, a Scottish army of 18,000 invaded Lancashire for the king. Cromwell and his colonels had spent the past year in a desperate attempt to quell rebellion all over the country and this invasion from the north had to be stopped.

The two sides met at Preston on August 17-18, 1648. The victorious side had an excellent chance of winning the second civil war. The Royalists chose Lancashire rather than Yorkshire because they believed that the hedged and enclosed land around Wigan and Preston would be a good defence from the terrifying cavalry charges of Cromwell’s ‘Ironsides’. They also expected more support from the local Catholic population; apart from Manchester and Liverpool, parliament had struggled for success in Lancashire during the war.

In reality, the local population remained neutral and fearful. It was to be a battle of outsiders that involved few Lancastrians. King Charles awaited the news as a prisoner in Carisbrooke Castle- a Royalist victory may well have saved his throne.

He had reason to hope; rebellions against Cromwell had appeared everywhere, and Cromwell himself was heading for Lancashire with a tired and depleted army after costly victories in Wales. The army had moved so quickly that the vital field artillery had been left behind.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPreston was one of the first battles were Cromwell was actually outnumbered by the enemy, and he went into battle with another major disadvantage.

It had rained so much in early August, and so that the waterlogged ground did not favour battle by cavalry charges. Cromwell’s favourite and most famous weapon of war was unavailable. Cromwell had already gained his reputation as a military genius before 1648, but whether he deserved it or not, brilliant military tactics were not needed at Preston.

The leadership of the Royalist Duke of Hamilton was terrible. He squandered his numerical superiority by splitting his army in two, and strung them out in a long line that reached to Wigan. Local commanders did not believe Cromwell could get from Pembroke - another vital victory- to Preston in so short a time. They only realised their mistake when Cromwell attacked the divided army on the morning of August 17, in the area which is now Fulwood, cutting of their retreat to Scotland and forcing them into the centre of town.

By the first day, after appalling hand-to-hand fighting of the most basic and grisly sort with muskets, swords and pikes, and with dead bodies and dying horse blocking the streets, Cromwell’s army secured the bridges over the Ribble and the Darwen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBlood ran through the streets and the rivers. The poet John Milton, who admired Cromwell, felt the bloodshed in Preston should be commemorated in his sonnet To Cromwell

While Darwent streams with blood of Scots imbru’d

At one point the Scots took advantage of higher ground to bombard Cromwell with stones and slates. Cromwell was a brave man; the kind of bravery you have when convinced God is on your side, but he could have died on that day, and our history would have been much different.

Both armies settled down for the night in the pouring rains and storms, and the bloodletting continued the next day, with the king’s army making a fighting retreat to Wigan while the other half of the Royalist army debated about whether to help.

It was not just the terrain that made the fighting bloody. There was a particularly hatred from Cromwell’s ‘godly’ soldiers, who could only conclude that these Scots were opposing the will of God by starting a second civil war after been decisively beaten in the first one.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey also hated and feared those they called ‘papists’ or ‘malignants’, Catholics and English Royalists. In earlier battles, quarter –the right to surrender with your life- would have been offered, but not here.

It was also horribly one –sided. Two thousand people were killed in the battle, a much more intensive death count than other civil war battles; all except 100 were royalists.

The cavalry, which could not win the battle, was used for their more traditional purpose of chasing and killing the retreating enemy. The thousands of captured soldiers who had volunteered for the king’s armies were sent to New England and Barbados as ‘indentured servants’- one tiny step up from slaves.

If you wish to follow the footsteps of Oliver Cromwell in Preston today, then the best place is Cromwell’s Mound.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese earthworks would have provided shelter for infantry soldiers and emplacements for guns, and are still visible today and protected by Historic England.

It is said that Cromwell himself directed some of the battle there, perhaps standing at the same spot where the Lancashire Post is today. A week after the Battle of Preston, the House of Commons agreed to talk to the King a once more about a settlement. However, it was not Parliament which was in control now; it was the army.

Preston was the place where the hopes of Charles I were finally snuffed out, and those who were prepared to consider his execution gained the upper hand. This makes Preston the most important battle of the civil war.

* James Hobson is the author of Following in the Footsteps of Oliver Cromwell (Pen and Sword £12.99)