Life behind bars with former Preston Prison and Strangeways governor: From counterfeit pottery to the UK's deadliest riot

It's the early '70s and Brendan O'Friel, deputy governor of Preston Prison, is overseeing a quiet evening. "We didn't have much going on and a senior officer told me that he'd got one of the prisoners, who was quite proficient on the guitar, to play to all the prisoners on the sound system," says Brendan. "It was something other than being locked up in a cell.

"The relationship between staff and prisoners was not, as some people might think, standoffish," adds Brendan. "There was a degree of give-and-take."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt's safe to say that The Shawshank Redemption's Andy Dufresne would have liked Brendan O'Friel. Born in the Isle of Man and educated at Stonyhurst College in Clitheroe, Brendan joined the prison service in 1963 on a wave of enthusiasm to do everything he could to improve it and refocus the penal experience towards rehabilitation.

"I was doing law at Liverpool University and visited the old Home Office-approved schools [residential institutions for young offenders]," explains Brendan. "I was appalled by what I saw and, as a bright-eyed, bushy-tailed youngster, I thought I could do something about it. A career with the prison service sounded interesting and offered me the chance to improve things.

"While it was quite unlike the sorts of careers most of my contemporaries were getting into, I wanted to make a difference," he adds. "I've always been interested in people and you get a very interesting, if sometimes very irritating, cross-section of people in prison."

After six weeks' training - "we learned a lot, not necessarily all of it right" - Brendan got to work.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I started at Lowdham Grange in Nottingham, an open-borstal establishment for young offenders," says Brendan. "After about two years, I came up to Manchester to work in Strangeways. The two experiences could not have been more different for a wet-behind-the-ears youngster learning the trade. But it's like any profession: you have a lot of learning to do in the beginning."

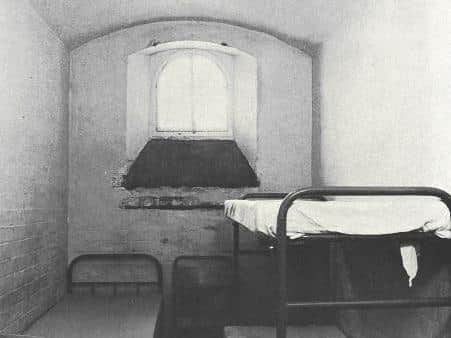

In 1972, he was appointed deputy governor at Preston Prison, where he found an overcrowded prison built for 400 inmates but housing 700. With the prison impacted severely by the three-day week caused by the miners' strike, Brendan worked closely with the governor and started a learning process that was to equip him well over the next 30 years.

"The governor was this quite unique chap who had been there over 10 years, which was unusual," says Brendan. "He was ex-Indian Army man and was excellent with staff and prisoners and I learned a huge amount from him. It was really interesting working with some of the older prisoners, who'd been in and out of the prison system for 20/30/40 years, too.

"Trying to have some positive influence upon these sorts of characters was a real learning curve for me," he adds. One instance sticks out. In the workshop, prisoners were tasked with sewing mailbags and a group of the older prisoners, whom had become well-known to the long-serving members of staff, were often allowed to sew outside in summer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"You'd have thought the staff would be sticks in the mud but they'd let the prisoners work outside in the sun to get some fresh air," says Brendan "That was an eye-opener to me about how flexible staff could be, what a difference it made to everybody, and the good response it could get from prisoners.

"I relished the the challenge of managing people and, by in large, everybody behaved reasonably well," he adds. "Apart from in 1972 when a sort of prisoners' union movement arose..."

Determined to demonstrate not through rioting or violence, some 600 prisoners simply sat down and refused to move whilst out in the exercise yard. "They refused to go in," says Brendan with a laugh. "But we managed it well - the principal officer in charge was an old Polish wartime pilot who'd flown Spitfires. Whereas others might have got worried, he just laughed at them.

"In the end, a few of the older prisoners saw the funny side of the whole thing as well as asked to go in, which meant about half the prisoners followed them," he adds. "Not taking things too seriously was a good lesson and senior officers being prepared to be flexible was the key."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1980, Brendan landed his first role as governor of a prison: Featherstone near Wolverhampton.

"It was obviously very exciting to have your first command as a relatively young governor at about 39, and it was a great experience," he says. "We had good conditions and gave prisoners a more positive experience, which was an achievement.

"There was one really funny story which came from a pottery class," he adds. "We had the prisoners making pots in the style of Bernard Leach, the very famous artist, and - by some design or other - some prisoners took these pots home with them after they were discharged and the pots ended up being sold as genuine Bernard Leachs!

"The auction houses had quite a bit of egg on their faces!" Brendan says, chuckling. "All these great experts fooled by prison pottery!"

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut soon, another stint at Strangeways beckoned. And eventful isn't the half of it.

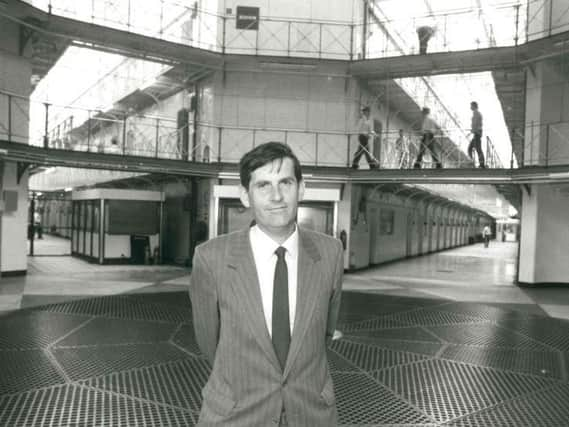

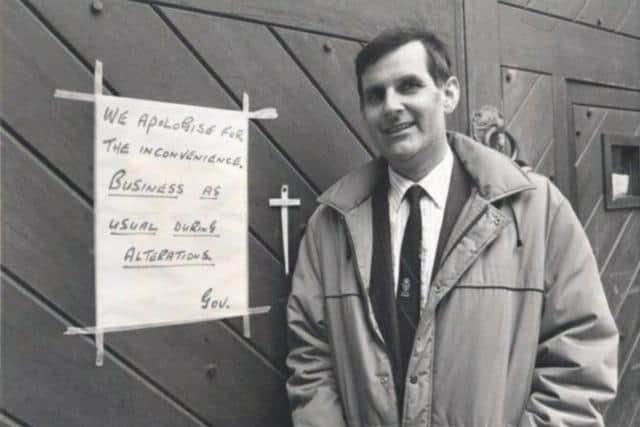

"We made huge progress in trying to reform Strangeways and did away with a lot of bad working practices," says Brendan of his time as governor at the prison. "It made a huge difference which is why, when the riot occurred, I was so mad."

In 1990, Strangeways - suffering from terrible overcrowding with 1,800 prisoners cramped into the 1,00-capacity establishment - was the scene of the UK's worst prison riot. A 25-day affair, the incident saw one prisoner killed, 47 injured, and 147 prison officers hurt. Some £55m-worth of damaged was caused.

"Things were still very bad, but we'd done an awful lot and prisoners knew damn well we were trying to make things better all the time," says Brendan. "And what do they do? Some idiots kick off and ruin everything by create mayhem. That there was only one death, given the violence, was quite remarkable. It was deeply frustrating.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"The violence prisoners meted out to each other... the way the sex offenders were beaten up by prisoners who, quite frankly, were no better was absolutely disgraceful," he adds. "I called it 'an explosion of evil', which crystallised what I thought at the time and still do.

"But it never diminished my belief in the fact that greater autonomy and faith in rehabilitation was the correct approach. It was and is the right thing to do."

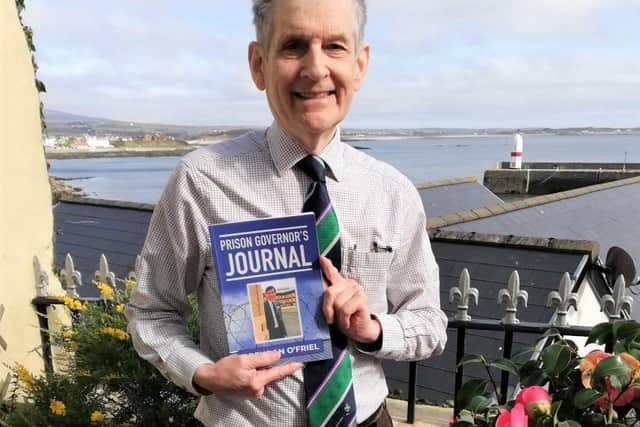

That outlook is one Brendan extols to this day. His recently-published book, 'Prison Governor’s Journal', offers a unique take on his variegated career and a wider view on critical prison issues dating back to WWII, most of which have been largely ignored by political and parliamentary scrutiny.

"The prison service has become overwhelmed," says Brendan. "Politicians trying to sound tough rather than looking at prison as a way of protecting the public is terribly sad because it means that, rather than rehabilitating prisoners, we've tended to warehouse them. And a lot of them have probably been damaged by the whole experience.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"The penal system is not being allowed to do it's job and, often, it's making people worse, not better," he adds. "We're sending too many people to prison for too long. Nobody who's been a prison governor would argue that we don't need prisons, but the numbers are now completely ridiculous. The whole thing is out of control."

It's hard to argue with such an assertion when one examines the facts. Since 1965, the prison population in England and Wales has increased by 175% despite the population rising by just 31% in the corresponding period. There are now more than 83,000 people incarcerated in England and Wales.

"What politicians don't do is actually look at what's causing the problem and whether there's a way of solving it," Brendan says. "They say they're going to be tough on crime but all they do is make the situation worse because the system is already struggling because of a lack of funding. A focus on dealing with people is much more significant in terms of stopping crime.

"A lot more money should go to alleviating poverty; there are deep causes of crime which are often to do with deprivation and a lack of opportunity," he continues. "That's why education is so important for people who do end up in prison. I'm all for them working very hard, but work has to be purposeful."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhilst terrible for the penal system, the Covid pandemic should be seen as a chance to instigate radical change, according to Brendan, who argues that the highly-consequential inability of the penal system to reduce re-offending generates a continuing threat to public safety. But good advice is only effective when heeded.

"I always did my best," says Brendan, who is in his 80s and lives on the Isle of Man. "You look and think about the things you could've done better, but I'm very lucky to have had the chance to work in the prison service for as long as I did and to have escaped in one piece.

"I'm grateful for that."