Is social media messing with children's morals?

More worrying, perhaps, than the amount of time spent online, are the findings that suggest social media use can actually influence users' personality and character. Recent research, for example, shown that there is a link between social media use and narcissism, and that the use of social networking websites may have an adverse effect on social decision making and reduce levels of empathy.

With this in mind, one of our latest research projects at the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, looks at the impact social media has on young people’s character and moral development, and aims to understand the benefits social media can have on development.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile the project is still ongoing, the first stage of our research involved a “parent poll” of 1,738 parents of 11 to 17-year-olds from across the UK asked a series of questions on their feelings around social media, and the moral (or immoral) messages that appear online. Our findings so far indicate that parents’ attitudes towards social media are largely negative – over a half of parents we questioned agree that social media “hinders or undermines” a young person’s character or moral development. While only 15% of respondents agreed that social media could “enhance or support” it.

Oh so social?

We also asked questions about parents’ own social media use and found that parents who regularly use social media reported a lack of “positive character strengths” on there – such as self control, honesty and humility. Instead, parents said they see a lot of anger and hostility, along with arrogance and ignorance on social media sites.

However, it isn’t all doom and gloom, because our research also shows that social media can be a source for good. Nearly three quarters of the parents who use social media on a regular basis reported seeing content with a positive moral message at least once a day – including humour, appreciation of beauty, creativity, kindness, love and courage. And it could well be, that viewing this type of positive online content could have a positive influence on young people’s attitudes and behaviours.

This is because on sites such as Facebook and Twitter, users often come across new perspectives and circumstances – such as different religions, cultures and social groups. And exposure to these situations online could actually help young people be more understanding and tolerant – and in turn develop their empathy skills. This is because it allows them to view things from other people’s perspectives, in a way they might not be able to in “real life”.

Moral support

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

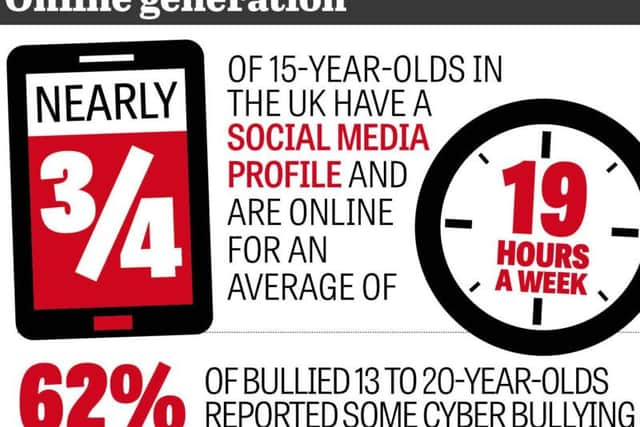

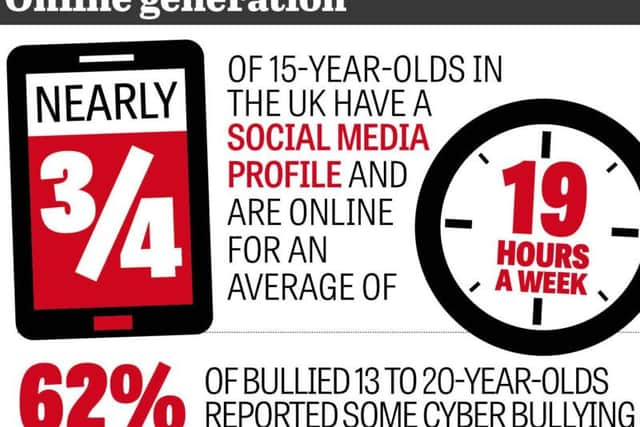

Hide AdOf course, this translation from exposure to empathy may not always follow – which can be seen in the high rates of cyberbullying. According to a 2015 report, 62% of 13 to 20-year-olds who had been bullied reported some degree of cyber bullying – which shows that empathy doesn’t always play a part in online environments.

Then there is the issue that the very nature of the internet, with it’s perceived invisibility and anonymity, can also mean people act differently online, compared to how they would in real life. This can lead to “moral disengagement”, where people are able to act in an immoral way while still viewing themselves as a moral person. And it is this “disengagement” which is thought to encourage cyber bullying behaviours.

But while it may be tempting for some parents to just ban social media use altogether, it is unlikely to be a successful strategy in the long term – social media is not going away. Instead, we need to better understand the relationship between social media use and a young person’s character and moral values. And through our research, we hope to be able to offer constructive evidence-based advice on exactly this.

Because it is clear that the online environment is a moral terrain which requires successful navigation. By understanding how boulders such as moral disengagement can be avoided, we can help to create a safer and more even path for young people to negotiate.

Research Fellow within the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham

This article was originally published on The Conversation