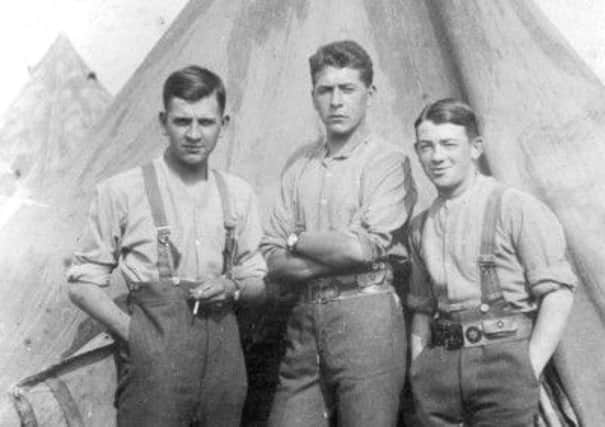

Allen Evans: The boy who lied about his age to join the army

He was 17 in 1971 when his grandfather died but he recorded for posterity some of the old man’s recollections of his experience in the First World War.

Allen Evans lied about his age to join the army. Many years on he did not dwell on the horror or play up his part in the fighting.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut, thanks to Nigel, he is a powerful witness to a terrible conflict.

Soldier boy Allen Evans was just 15 when he managed to enlist.

The first time he tried to persuade the recruiting sergeant to sign him up he was told to go away and grow up a bit.

But determined Allen tried again and within weeks he was in France.

He was supposed to be 18.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTravelling by train in 1914 the young soldiers sang lustily - one half of the carriage did Tipperary and the rest sang Pack Up Your Troubles at the same time.

Their introduction to the horrors of the front line was brutal.

In the trenches for the first time he and his mates from the Lancashire Fusiliers were told to keep down where the parapet was low.

Someone in front of Allen failed to do so and was shot through the head.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAllen recalled: “The first night I spent in the front line the artillery made me so nervous that I could not sleep. Someone gave me my first ever cigarette. I felt more at ease and was able to sleep. I smoked from then on.”

Sometimes the trenches were 100 or 200 yards apart.

Sometimes so close it seemed that Allied and German men might reach across with their rifles and touch.

One night Allen went on a night raid to capture prisoners for interrogation.

“An advance party had staked out white tapes a foot above the ground leading across No Man’s Land. We ran our hand along them so we did not get lost in the dark. If a flare was sent up by the Germans we had to stand stock still. We carried long tubes of explosive called Bangalore Torpedoes to blow a path through the enemy barbed wire. We jumped into their trench and took prisoners. The man who led the raid got a medal.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne night Allen was digging a trench in No Man’s Land when he accidentally struck a friend a terrible blow with a pickaxe.

“He was taken away unconscious and I thought I had killed him. Many years later I met him by chance in the Isle of Man and realised he had recovered and survived the fighting.”

Appalling losses were suffered at the Battle of the Somme.

Allen and his mates waited in a trench for the order to attack.

“The first wave went over the top and disappeared. We never found out what happened to them. The second wave was machine-gunned in No Man’s Land. The third wave was also cut down.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was due to go over in the next wave but we were ordered to stay in the trenches.”

After the carnage became known at home in Salford, Allen’s mother wrote to his CO and asked that he be sent home. He was a seasoned soldier at 17 years of age and still under age. The CO replied that he could not be spared.”

Mud like quicksand and the terrible poison gas attacks were among the problems faced by young men like Allen Evans.

“Some men could not stand it and to get out they would lie down, put a rifle to their foot, and shoot off their toe.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe only time Allen was in hospital during the war was when he got tannin poisoning drinking gallons of tea during a spell working in the stores!

He had one home leave and his mother was astonished to see him. He was home for just a weekend.

On the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918 Allen enter a ruined village recently occupied by the Germans.

“They had laid a huge mine all ready to explode so we were lucky not to be killed on the very last day.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite all he had seen Allen never doubted the necessity of the war which he believed was necessary because Germany had been the aggressor by invading Belgium. He believed the Allies might well have lost if the Americans had not come in.

Allen Evans started his working life as a trolley boy on the trams in Salford.

He played rugby league and went to Blackpool in 1926 to join the borough’s own police force.

During World War Two he was the police officer in charge of civil defence and was a long-serving detective in the resort.

He reached the rank of superintendent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter retirement he served for years as a Liberal member of Blackpool Council.

He had played cricket for the police and became an enthusiastic golfer. He was a Freemason.

For many years he and his wife Nellie lived in Lomond Avenue, Marton and had two daughters.

One was Mrs Ida Hampson of Corbridge Close, Marton.

She said: “My father had the quality of leadership. He was a fair man and he was as straight as a die in his dealings with other people.”