Race row sent hundreds on strike in Preston

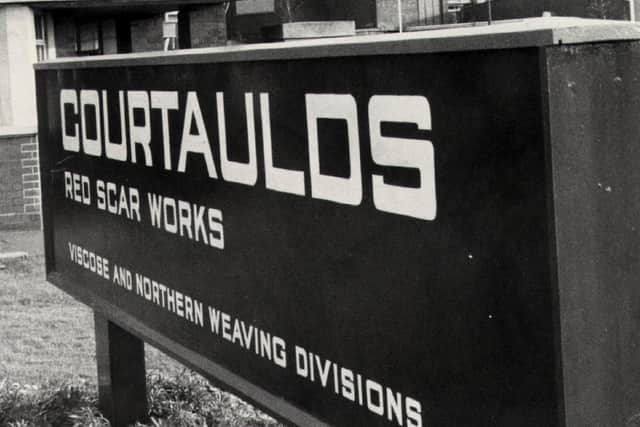

After opening in 1939, the Courtaulds plant at Red Scar became one of Preston’s largest textile mills, employing 3,000 people by the mid-1960s.

Approximately one-third of the employees were Asian and Caribbean workers, concentrated in one stage of the labour process.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn May 24, 1965, workers in the tyre-cord spinning department commenced a sit-in. The dispute originated with a controversial ‘speed-up’ plan, by which each worker would become responsible in effect for one-and-a-half machines – a 50 per cent increase in production norms per capita – for a wage rise of just 3d per hour.

Workers from Pakistan, India and the West Indies were especially affected by this change and, within four days, 900 migrant workers – constituting almost one-third of the factory’s total workforce – were on strike.

What originally appeared a straightforward dispute between workers and bosses quickly became entangled in a public power struggle between the strikers and the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU).

Immediately refusing to support the strikers, TGWU shop stewards complained that Indian and Pakistani workers rarely attended branch meetings. There was only one Indian shop steward at Courtaulds in 1965.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFurther distancing the union from the strikers, TGWU regional officer Bill Heywood declared they were not prepared to support unofficial action. He stated they were only prepared to lodge support if the strikers accepted the union’s advice and returned to work under the agreement the shop stewards made on their behalf.

Within a week, three TGWU officers, including Heywood, were jostled and heckled at a rowdy meeting of the strikers at their adopted home, the Continental Cinema on Tunbridge Street.

Migrant strikers organised autonomously in a self-styled Action Committee under Mr AA Chaudhry, threatening to withdraw from the TGWU and ‘fight the case on our own shoulders’.

The Action Committee wrote to Courtaulds management, complaining that increased workloads and new machinery had worsened conditions, but the firm’s labour officer Robert Law dismissed their complaints and patronised the striking workers: “They are gentle folk, on the whole, and are good workers when they wish to work.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe intervention of international activists raised the strike’s profile. Visitors to Preston included representatives of the Jamaican and Pakistani High Commissions, the Commonwealth Citizens UK Association (CCUKA), and the Racial Adjustment Action Society (RAAS), including radicals Roy Sawh and Michael de Freitas.

CCUKA chairman Malik Khaliq, an experienced shop steward from Bradford, implored strikers to reject union officials’ offers to mediate. In a rallying cry during the strike’s second week, Sawh proposed forming a trade union exclusively for black workers.

De Freitas had founded the RAAS just months before the Courtaulds dispute arose. In 1967, he was the first non-white person to be convicted under the Race Relations Act.

Arrested for his role in attacks at a commune in London in 1969, de Freitas’s bail was paid by John Lennon. After returning to his native Trinidad in 1971, de Freitas – known by this juncture as Michael X – was convicted of murder and hanged in Port of Spain’s Royal Jail in 1975.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe lack of solidarity action among workers at Courtaulds enabled opponents to represent the strikers’ motivations as the malign agenda of racial separatists.

Approximately 2,000 white workers at the plant worked throughout the strike, mitigating its impact on the firm’s production. The union rejected strikers’ calls for a mass meeting of all Courtaulds workers.

Portrayals of the strike as a bandwagon for radical racial politics gained some traction locally. In a letter to the Lancashire Evening Post, Mrs Holden, of Chorley, declared that the ‘nation’ would ‘ruthlessly oppose’ a separate union ‘for coloured people’, and blamed Sawh ‘and his co-agitators’ for ‘taking advantage of a trade dispute, for political ambitions’.

Newspaper reports quoted de Freitas stirring strikers at a mass meeting by declaring: “We have one enemy: the white one who is oppressing us.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdResidents near the strikers’ HQ at Sergeant Street, in Deepdale, regarded strike meetings as a public nuisance which could aggravate racial tensions. Police were regularly called to the scene to keep the peace.

The strike committee’s tactics were eclectic. After fruitless appeals to the TGWU, the committee first invited an American lawyer to seek an injunction against management and shop stewards. Next, they implored Labour’s Minister of Technology (and TGWU General Secretary) Frank Cousins to advocate on their behalf.

With no resolution in sight, but as many as 250 workers now back at work, the strike leaders played their final card in the strike’s third week, when Khaliq and Chaudhry announced they would travel to Downing Street to commence a hunger strike. Some 110 strikers pledged to join this hunger strike.

The strike’s abrupt and somewhat mysterious ending after three weeks reflected the confusion which had reigned among strikers and the local public throughout.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a bid to end the hunger strike, TGWU officials had intervened secretly with Courtaulds bosses in London on June 10. The following day, the strike committee reluctantly agreed to a settlement.

Battle-weary and mindful of the strike’s diminishing numerical strength, the remaining strikers met at the Continental Cinema, where 218 of approximately 240 in attendance voted to return to work. Khaliq was unimpressed by union representative Robert Davis – a ‘swollen-headed trade union official’ – but declared himself hopeful that workers would yet ‘receive justice’ with improved working conditions at Courtaulds.

Dr Jack Hepworth is Associate Lecturer in History at UCLan. He is researching the Courtaulds strike, including interviewing former Courtaulds workers who remember or participated in the strike. Anybody interested in being interviewed for the project can contact Jack by phone (01772 432 077) or email ([email protected]).