Lost story of Preston's slave traders

The dominance of London, Bristol, Liverpool and Lancaster in the slave trade of the 18th century has obscured the fact that other, smaller ports also had a share in the barbaric trade.

Published accounts of the slave trade rarely mention the small ports, partly because much of the detailed information comes from the period of abolition, when most of the small ports had given up the struggle to compete with the four great ports.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut in the middle of the 18th century, Liverpool men were well aware of the efforts of nearby ports to take a share in the slave trade, as well as other colonial trades.

For example, in the early months of publication of Liverpool’s first successful newspaper, Williamson’s Liverpool Advertiser, there is evidence of northern ports competing with Liverpool’s slave trade.

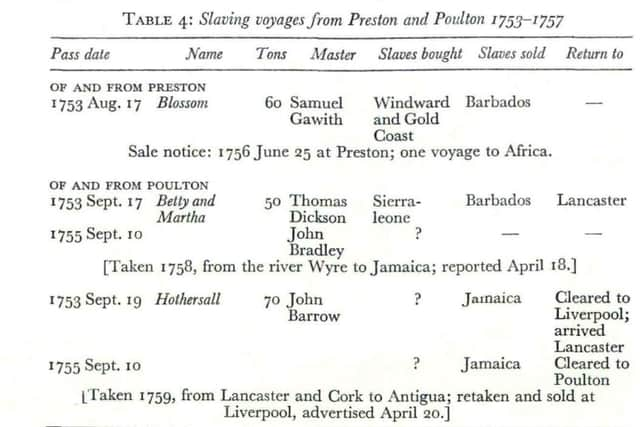

On June 25, 1756 there was advertised for sale at Preston: The good snow or vessel called the Blossom, Samuel Gawith commander, burthen 100 tons more or less, built at Preston, and has been one voyage only (on the coast of Africa), a very strong and tight vessel of proper dimensions and every way compleat for the Slave Trade... The vessel and her materials may be viewed... at Lytham in the River Ribble where she now lies.

Lancaster had a considerable trade with the West Indies, but it is surprising to find from a government return for slavers cleared from British ports between 1757 and 1776 that Lancaster was the port most involved in the slave trade after Liverpool, Bristol and London, both in numbers of vessels and regularity of sailings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAgainst 1,540 vessels cleared from Liverpool, 691 from London, and 457 from Bristol, during the period 1757 to 1776 inclusive, Lancaster numbered 86. The next highest totals were for Whitehaven with 46 vessels cleared between 1758 and 1769, and Portsmouth with 31 between 1758 and 1774.

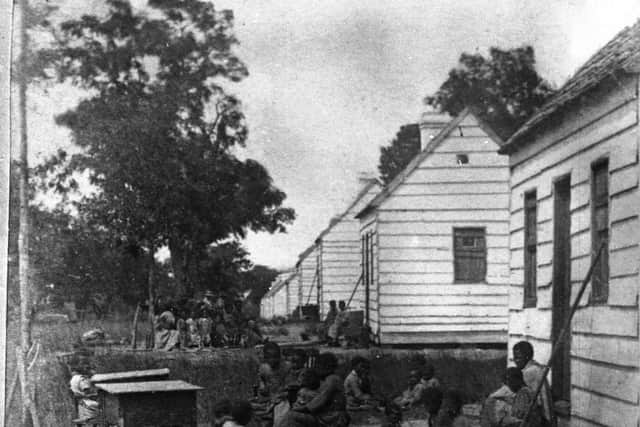

Though Liverpool, early in the 18th century, began to challenge London and Bristol in the barbaric business, other Lancashire ports were slow to follow. Regular trade from Lancaster thus began only in 1748 and from Preston and Poulton (which were both registered under the customs port of Poulton until 1760) in 1753. In the four years up to 1757, three vessels embarked on five slave trading ventures from Preston and Poulton.

The attraction to the brutal trade for new entrants must have been the prospect of imitating the success of the Liverpool merchants. In spite of the check to trade caused by the War of Jenkins’ Ear in 1739, and by the entry of France into the war in 1744, the slave trade from Liverpool rose steadily.

Clearly, there were profitable markets for slaves in the West Indies and the Southern American colonies, though during the war vessels loaded with enslaved Africans were particularly vulnerable to attack, and particularly valuable prizes for Spanish and French privateers in the West Indies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter the war, not only were there the British colonies to be supplied with slave labour, but also, by a renewal of the Asiento Treaty with Spain, the Spanish colonies. The merchants of the small Lancashire ports were as capable of appreciating the post-war demand in the trafficking of slaves as were the merchants of Liverpool. All had some experience of colonial trade to the West Indies and the colonies.

Lancaster at the end of the 17th century had begun a tobacco trade with Virginia, followed by trade with the West Indies. When the Virginia trade fell into the hands of Liverpool, Whitehaven and Glasgow, there was still a good trade in the West India staples of sugar, rum, coffee and later raw cotton, both for use in Lancashire and for export to Ireland and elsewhere.

The port of Poulton, with the two estuaries of the Ribble and the Wyre both difficult to enter and navigate, seems at first sight a doubtful prospect for colonial trade. But the important market town of Preston and the lesser township of Kirkham, lying between the two rivers, were developing an important linen industry, and behind Preston was the important East Lancashire textile area, with its linens, and linen-woollen and linen-cotton mixture cloths.

The growing population could offer profitable trade in colonial goods, and with experience in handling Baltic shipping bringing flax and hemp, timber and iron, in the 1740s Preston and Poulton merchants began to send their own ships to the colonies instead of importing such goods through Liverpool or Lancaster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne reason for the entry of the small north western ports into the slave trade in the 1750s was that their ventures were cheaper than their rivals. Shipbuilding on the north west coast was reckoned to cost less, and Chester, Liverpool and Lancaster built ships during the 18th century for ports elsewhere, including London.

There were local timber supplies in the hills and poor lowlands of Wales, Cheshire, Lancashire and Cumberland, supplemented by Baltic and American imports. This timber supply had in the late 17th century attracted some of the Midlands iron industry which was running short of charcoal timber, and allowed the development of the Furness iron ore deposits.

Thus iron fastenings used in some parts of the ships, iron fittings for masts and rigging, and anchors and chain cables, were easily available. A local linen industry nourished, so that, for example, the Kirkham merchants could send sailcloth to London for the use of the navy as well as supply local markets for canvas and other linens.

In addition to the low cost of outfitting for sea, Lancashire had increasing advantages in preparing cargoes for the slave coast. One of the most important of the trade goods required for the purchase of slaves was cotton cloth of various types in bright colours and patterns.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA shortage of Indian-made cotton fabrics originally in demand in Africa allowed Lancashire manufacturers who imitated East Indian goods to expand and seize part of the African market. Thus the merchants of Lancashire’s small ports had an incentive to compete with Liverpool in the slave trade.

They were close enough to Liverpool to appreciate the profits being made in the colonial trade and human trafficking, and they were close enough to the centres of supply of exports which Liverpool merchants used.

They also had connections in the colonies, and markets for the return cargoes in the newly expanding industrial areas of central and south Lancashire. The growth of the textile manufacturing area of East Lancashire, coupled with the growing population’s demands for tobacco, sugar, rum, dye-stuffs and other colonial goods, prompted merchants in Poulton to build, in 1741, a warehouse at Skippool on the river Wyre specifically for goods from Barbados, and from 1742 vessels, mostly owned by the merchants of Kirkham and Preston, began to trade from Poulton and Preston to the West Indies, with Baltic voyages to bring in flax and hemp.

Thus the local merchants would save costs of using the port of Liverpool, which included ‘town dues’ payable to the corporation of Liverpool on all goods handled in the port which did not belong to a freeman of Liverpool.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter 1750, as far as present evidence indicates, sailings to the colonies from Preston began, but arrivals at Preston and Poulton are often difficult to identify from Lloyds List and from newspapers, to whom such a small trading area was unimportant compared with Lancaster and Liverpool.

Preston and Poulton vessels sometimes arrived at these ports perhaps because both towns had sugar refineries which supplied the retail trade of the Preston area, or because Preston and Poulton vessels might be landing goods for merchants at Liverpool or Lancaster taken as freight, before returning to their home port with the cargo consigned to the vessel’s owners.

The number of slaves carried by Preston and Poulton vessels was not large. One, named Betty and Martha, was used as a slaver ship and on her first voyage is reported in Lloyds List on July 4, 1755 to have landed at Barbados only 65 slaves, a figure so small as to appear a misprint.

Another vessel, Blossom, sailing from Lancashire is reported in the same issue of Lloyds List as landing 131 slaves at Barbados, while another vessel, the Hothersall, is recorded in the Jamaica colonial naval officers’ lists as landing 150 in 1755 and 135 in 1756, figures which are more likely to be accurate than those in Lloyds List.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is difficult to deduce anything about the profitability of these voyages from human misery, but in view of the small number of slaves carried, the time spent on the voyages, all over 20 months, seems too long.

By comparison the Thetis of Lancaster of 40 tons, smaller than any of the Poulton and Preston vessels, had a pass application on February 23, 1759, landed 212 slaves at South Carolina in September, and had a second pass application on December 18, 1759.

The enslaved people were bought on the Windward and Grain coast, the same area in which the Betty and Martha (and presumably the Hothersall), and the Blossom bought their slaves.

What is clear is that the Poulton and Preston merchants did not persevere with the trade.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe fate of the Blossom after the sale advertisement was published is unknown, but both the Betty and Martha and the Hothersall were employed on direct voyages to the West Indies, in which the first Betty and Martha and the Hothersall had been engaged previous to the venture into slave trading.

Other Poulton and Preston vessels continued in the West India trade until the mid 1760s. Though there were no more slavers from Poulton and Preston, the interest of the Kirkham linen manufacturers in the slave trade did not cease and the town’s Langton and Shepherd were part-owners between 1767 and 1771 in five slavers from Liverpool. By 1780 the colonial trade from Preston and Poulton had ceased.

* Abridged and edited from The Slave Trade from Lancashire and Cheshire Ports outside Liverpool c.1750 1790 by MM Schofield MA.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.