Diary of a First World War soldier found in an attic

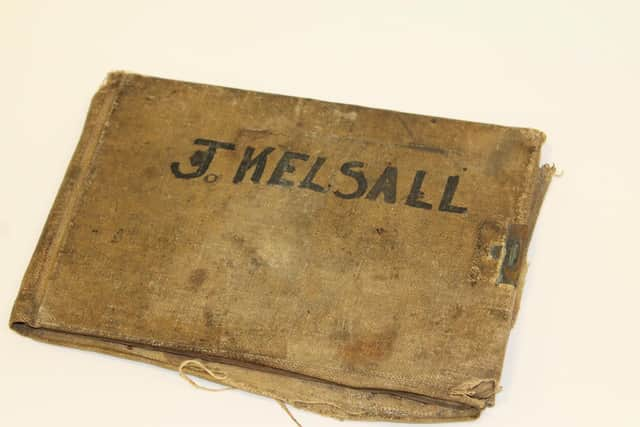

Sergeant Joshua Kelsall’s stained, canvas-covered diary of his experiences in war-torn France between August 7, 1914 and February 3, 1915 lay undiscovered until November 1993, when it came to light among the effects of his son Rowland after his death.

Rowland’s widow gave the diary to Joshua’s daughter Mrs Freda Howarth who, after a casual glance at the tattered cover and faded pencil jottings, thought she had at last found her father’s legendary old recipe book of herbal remedies which she has heard about and had vanished years ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCloser examination of the more legible entries showed it to be something very different and rather puzzling until she realised it was a diary of her father’s experiences in the trenches of the First World War, recorded long before she was born.

Closer inspection revealed the diary to be a day-by-day and, in parts, even hour-by-hour record written between lulls in bombardments or during relief from frontline action.

Joshua was no raw recruit, he had first enlisted in 1902 and saw service in Egypt between 1903 and 1905, after which he was a reservist.

He was thus a trained, experienced infantryman – and a 31-year-old family man – when recalled to the colours on August 5, 1914. A few days later he was among the first members of the British Expeditionary Force to land in France.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis brothers William, Joseph and Alfred volunteered and were soon in the trenches. George, aged 18, and Robert, 14, remained at home.

George (who, family legend had it, turned cartwheels when war was declared, being excited at the prospect of soldiering), wanted to volunteer but was strictly forbidden by his mother.

As the war progressed, taking its immense toll, conscription was introduced in 1916 and George received his call-up notice. Their mother Kate, growing increasingly concerned about her sons at the front, would not allow him to report.

When the men in uniform called at the house to take him, she made George hide in the attic. But he was later apprehended, taken into custody and held at the local barracks on Stanley Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKate was incensed. ‘They’ already had four of her sons and, odds being against them all returning, it was time to draw the line!

With a number of her women neighbours who had lost sons and husbands, she led a protest march to Stanley Street, where they demonstrated outside the barracks with placards.

Kate continued her public protest alone when her neighbours eventually gave up. But to no avail. George was sent to the Somme with the 1st Battalion, Loyal North Lancashire Regiment ,and was soon killed as her intuition told her.

She was later informed that he died on the night of March 7, 1917 trying to carry his wounded officer back to the lines after a bombing raid, both being killed by a mine. Kate’s remaining sons mercifully survived.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJoshua’s diary reveal a measure of contempt rather than hatred for the enemy, but for most frontline soldiers he was glad for the respite provided by the truce of Christmas 1914 which he vividly recorded.

As a corporal with the 9th Batalion, Rifle Brigade, he was wounded in France on September 25, 1915 and transferred to hospital in Sheffield.

In a letter to his wife, who at the time lived at 9 Alma, Street, Preston he wrote, “I was in the firing lines for two days and nights, as we just went into the trenches to make the charge as I was lying in a small hole about 20 yards from the German trenches.

“They only slightly wounded me in the chest, and I shall be all right in about a week. I have had the satisfaction of taking part in the biggest and bitterest battle that British Tommies ever fought.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJoshua junior was married to Mary Halfpenny and they had eight children. After returning from service in 1920, the family lived at Noel Square, Ribbleton, Preston.

It wasn’t the gunshot wound to the chest which permanently damaged his health, but the long periods spent in flooded trenches during the bitter winter of 1914-15. He contracted severe bronchitis (he called it a chill) with which he was first invalided back to Britain. It dogged him for the rest of his life, contributing to his death in 1936 at the age of 54.

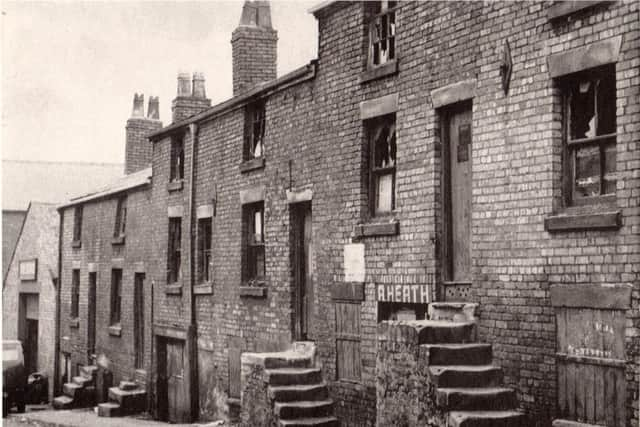

Joshua Kelsall was the eldest of 11 children of Joshua and Kate Kelsall of Snow Hill, Preston. The couple both worked as weavers at Horrockses cotton mill, in Preston.

Times were hard, wages were being cut and Joshua senior attempted to organise a protest by haranguing fellow workers from a box in the mill yard. This resulted in the Kelsalls both being ‘sacked and blacked’ and never afterwards able to obtain employment in the cotton trade.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJoshua, a keen botanist, turned to landscape gardening and became quite successful, he and Kate working and ‘living in’ (she as a ‘domestic’) at various large residences in the county.

This working arrangement was soon to end when Kate began to have children. A house was found in Ribbleton, Preston, and while Kate was involved with a growing family, Joshua worked away most of the time due to the nature of his job.

On September 5, 1920 Kate received a knock at the door from the police to inform her that her husband had met with a sudden and violent death in Brockholes Wood on the outskirts of Preston. He had been shot by Robert Hargreaves, of Raikes Road, who mistook the sleeping Joshua for a rabbit in the dim early morning light.

The inquest disclosed Kate and her 61-year-old husband had been living apart for 14 years and that he “gained a living by getting ferns and making wreaths, buttonholes and bouquets which he sold about town.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was also reported to be in the habit of sleeping in the open in Brockholes Wood. At the funeral, Kate, according to family there at the time, was distraught. Her arms across her husband’s coffin, sobbing uncontrollably, recalling earlier, happier days with her ‘Jos’.

Joshua senior was a Preston character with a reputation for his knowledge of botany. He collected and sold fresh herbs with guidance as to their culinary and medical use. He also taught himself the art of floristry.

He had a talent for art and an ambidextrous ability to draw, in mirror-like fashion, two perfect opposing images simultaneously. He could also transform potatoes into things of beauty. With deft strokes, he would quickly produce superb white roses with his penknife to hand out to an admiring audience. Such party tricks often earned him free beer.

A framed drawing of his showing two opposing greyhounds used to hang in a prominent place in The Old Dog pub in Preston. Hargreaves was cleared of any wrongdoings surrounding Joshua’s death and left for a new life in Canada three weeks later.

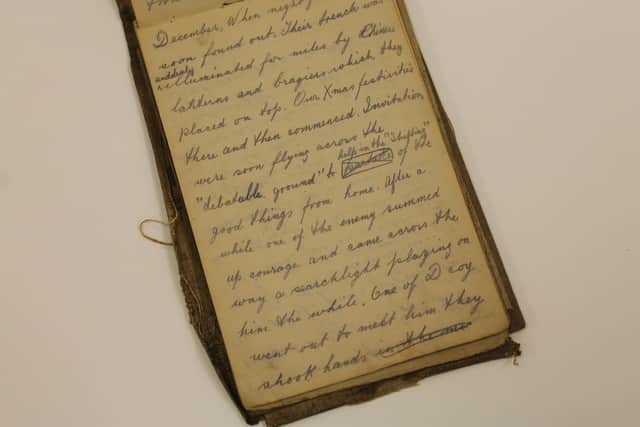

Joshua Kelsall’s diary, Christmas 1914

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was very little firing from the enemy all day on Christmas Eve. When night fell we soon found out why.

Their trench was suddenly illuminated for miles by Chinese lanterns and braziers which they placed on top. Our Xmas festivities there and then commenced. Invitations were soon flying across the ‘debatable ground’ to help in the shifting of good things from home.

After a while one of the enemy summoned up courage and came across the way with a searchlight playing on him the while.

One of D Company went out to meet him. They shook hands between the two lines to the accompaniment of cheers, songs and ‘War Whoops’ from a Battalion on our left – a sight seen once in a life time. Makes a lump come sudden in a man’s throat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThus emboldened both sides came out in the open, now lit up by several search lights, a weird sight.

There was little sleep as the carol singers of both sides made the most awful din. The Germans had good voices. They seem to be trained choristers.

One of their chaps gave us ‘For Old Times Sake’ and didn’t we join the chorus! Another, ‘Down South in Dixie’, both accompanied by a splendid cornet player.

After breakfast on Christmas morning parties of men went out to help the Germans bury their dead. We challenged them to a game of football. Their officers would not consent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey gave us cigars and picture postcards. We gave them a few tins of Bully, Cigarettes and other things as souvenirs. Quite a lot of them speak very good English.

One officer of ours told a German officer about the bombardment of Hartlepool and Scarborough. He could hardly believe it until our chaps sent his servant for newspapers.

Some of these chaps had the idea that they had only the British to beat, that Paris was in their hands, that the Russian Army was a thing of the past and Zeppelins had destroyed half of London.

“We heard of nothing but victories,” said a Sergeant Major in my hearing. We let them know the facts.

They made us an offer, said they would not shoot if we refrained from firing. We kept the agreement till they broke it by potting one of our chaps in the leg three days afterwards.