Lancashire man beyond the greatest war poem of all

They are perhaps the most famous words in 20th century British poetry, 'We Will Remember Them.'This powerful line is chorused around the world on Remembrance Day each year, to commemorate those who have died in conflict. But while the words are well-known across the entire globe, the poem they come from and its author, trace their roots all the way back to Number 1, High Street, in Lancaster.

It was there, on August 10, 1869, that Laurence Binyon was born to Reverend Frederick Binyon and his wife Mary in the house opposite the National Girls’ School.Laurence enjoyed an affluent childhood alongside his older brother John and his younger brothers Charles and Gilbert, with a cook, a housemaid, and a nurse all employed by the family.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite his Lancaster upbringing, he spent an increasing amount of time in Burton-in-Lonsdale, on the Yorkshire border, where his father was the vicar of the All Saints Church. Binyon later claimed that “I belong to the wrong rose – the red rose and not the white”, confessing, “my earliest recollections are of the hills and streams of the West Riding”.

He was a bright boy like his father, who had studied at Cambridge, and he excelled in school. The younger Binyon soon found himself studying Classics at Oxford. By the time he graduated in 1893, he was already an award-winning poet, but decided to follow his passion for history, and took up a job in the prints department at the British Museum.

He continued to write in his spare time, and over the next two decades his national reputation grew hugely. Binyon’s artistic flair seems to have run in the family, as he and his cousins – Stephen Phillips and Arthur Ransome – enjoyed parallel successes in their respective fields; Binyon’s collected poems, Phillips’ sold-out stage plays, and Ransome’s novels – including Swallows and Amazons – all receiving popular and critical acclaim.

Binyon’s work was so highly thought of that in 1913, upon the death of Alfred Austin, the Poet Laureate, he was suggested alongside the legendary names of Rudyard Kipling and Thomas Hardy as his potential successor. Then came the outbreak of the Great War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs the Germans swept through France in early September 1914, the French Army, supported by the elite soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force, desperately attempted to halt the enemy and prevent the fall of Paris. It was a successful but costly mission, becoming known as The Miracle of The Marne, and while Paris was saved, the heavy losses of British servicemen shocked and distressed the public.

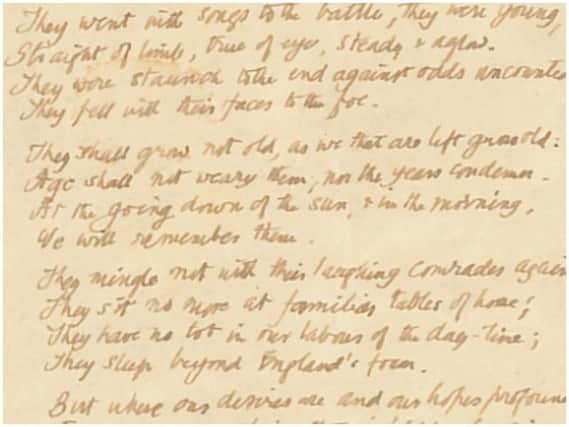

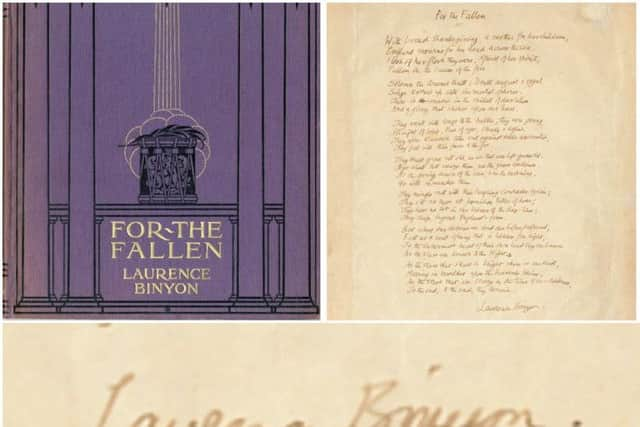

Days later, Binyon took a trip to Cornwall, where on a warm autumn evening, he sat among the grass and samphire on the cliffs at Pentire Head, which overlook the English Channel, and composed For The Fallen as, against this idyllic backdrop, he imagined the war raging on the other side. On September 21, 1914, For The Fallen was first published in The Times and was immediately praised as a solemn reflection of the loss the country felt.

Kipling called it “the greatest expression of sorrow in the English language” and Edward Elgar – Binyon’s close friend – set the poem to music in his famous requiem The Spirit of England. It is ironic that, while Binyon’s words had managed to capture the grief of the nation, the true horrors of the war had barely even begun. Although Binyon was too old to sign up to fight, he still wanted to play his part, and in 1915 he joined the Volunteer Civil Force, working as an orderly in the Temporaire de’Arc-en-Barrois hospital in France, helping the recovery of wounded soldiers.

By the end of the conflict, For The Fallen was one of the most popular war poems in Britain, and it began to be read at remembrance events around the country. It was deemed to be more suitable for services than other famous works because while it mourned the loss of servicemen, it spared their families details of the violence – unlike the poems of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe poem’s fourth stanza, considered the most moving, was inscribed on war memorials across Britain and France, and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission engraved tens of thousands of tombstones with the line: “At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them.” At the Menin Gate in Ypres, servicemen began to recite the fourth stanza at sunset every evening – a tradition which continues to this day.

But it was not until 1933, while Binyon was lecturing literature students at Harvard University, that For The Fallen received wide international attention. That year, at the Festival of Empire Remembrance at the Royal Albert Hall, the Prince of Wales recited Binyon’s poem in a speech which was broadcast to millions across the globe. Since then, his words, originally addressed to Britain’s professional soldiers lost in the first weeks of the Great War, are now used to mourn the dead of all conflicts around the world.

Binyon continued to work after the war, and as an academic he was a pioneer in western appreciation of Oriental art and culture, also completing highly respected translations of classical works like Dante’s Divine Comedy. Binyon passed away in Reading, Berkshire, on March 10, 1943, at the age of 73 from complications from appendicitis – an accomplished historian and poet whose words have given a voice to the grief of generations of people affected by war. But despite his success, Binyon always felt uneasy that the fame For The Fallen received had eclipsed the rest of his career and reputation.

“Is it fair to be judged on a few lines like that?” he once asked in a rare public appearance, “I have written other things.” But Binyon need not have worried... On this centenary year of the Allied victory in the Great War, as we prepare to hear the Lancastrian’s immortal words once again, we will remember him.