Teenage sailor who escaped death in the Battle of Jutland by minutes

By mid- 1916 the Great War had been raging on land and in the air for almost two years but aside from the odd tactical skirmish, little of note had happened between the two surface fleets in all that time.

That was until the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet clashed during a ferocious 24 hour period from May 31 to June 1 in what became known to the British as the Battle of Jutland and to the Germans as the Battle of the Skagerrak.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was to be the only time the two fleets met in such numbers and the fate of the battle and my grandfather-in-law’s destiny rested on just two things: communication and luck.

James Ernest Thomas reputedly ran away twice in his life. The first time was in 1914 when aged just 16 he enlisted with the Royal Navy as a boy sailor. His father was a Company Sergeant Major who would see action at Gallipoli but James, a strong swimmer, had a closer affinity with the water and an innate sense of adventure.

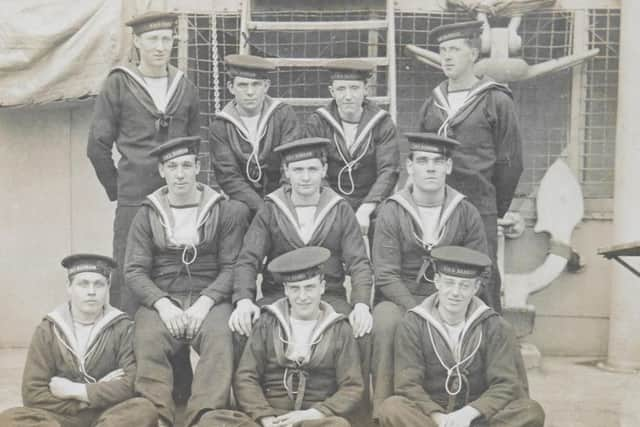

In 1915, after specialising in radio telegraphy, he joined a crew of 10 telegraphists aboard HMS Barham at Rosyth, near Edinburgh, where he would serve as an Ordinary Telegraphist,equivalent to Ordinary Seaman.

Barham then joined Rear Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas’s 5th Battle Squadron (5th BS) as his flagship in autumn 1915, alongside three other Super Dreadnoughts of the Queen Elizabeth class: HMS Warspite, Malaya, and Valiant.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe was no ordinary ship though. With a top speed of 32 knots and a crew of 1,016, she epitomised this new class of fast, manoeuvrable battleship, armed with eight 15” guns that were designed to outrun and outgun their counterpart German battle cruisers.

This squadron was part of a larger cruiser force led by Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty who in turn reported to the Commander of the British Grand Fleet, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe.

On May 30, the Admiralty had decrypted enemy signals ordering the U-Boats be temporarily stood down, while the German High Seas Fleet departed from Wilhelmshaven and Bremerhaven to enter the North Sea in an attempt to ambush and destroy the British Fleet.

Forewarned, Jellicoe’s ships set sail from their Scottish ports at Scapa Flow and Cromarty that evening to engage the Germans somewhere near the Danish coast.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBeatty’s cruisers and the 5th BS sailed from Rosyth at 10.08pm on May 30 planning to rendezvous with Jellicoe.

Churchill said of Jellicoe that he “was the only man who could lose the war in an afternoon” and so the public, political and military expectations of a major naval battle, which it was assumed Britain would naturally win, rested heavily on Jellicoe’s shoulders.

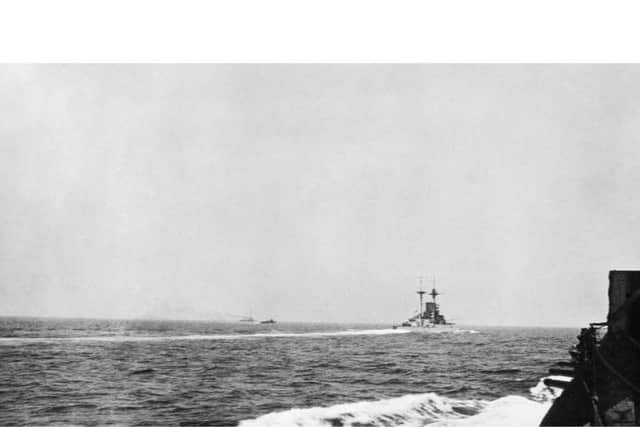

In the mid-afternoon of May 31, alerted by a possible sighting of the enemy, Beatty ordered his formation south to confront them.

HMS Southampton reported three of Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer’s battle cruisers heading towards them with the German High Seas Fleet close behind. Fearing a massacre, Beatty ordered a turn north back towards Jellicoe’s main force but delayed communicating this instruction to the 5th Battle Squadron for several minutes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBarham’s Captain, Arthur Craig Waller, realised the formation was separating. He pleaded through intense signal traffic with his squadron commander Evan-Thomas to turn north, follow Beatty and rendezvous with Jellicoe. The telegraphists on Barham including James were now frantically rushing signals back and forth to the bridge.

Eventually the 5th BS commenced their turn but were now well within the range of Scheer’s cruisers who began directing their fire at them shortly before 4pm.

Barham was now in the thick of the action and over the next hour, shells straddled the ships of both sides as each adjusted their aim. Amid the thunderous noise from the ship’s own guns, Captain Waller continued to exchange orders with his squadron commander.

Then, between 4.58pm and 5.10pm, Barham received six direct hits from the battle cruiser SMS Derfflinger. It was sometime during these salvos, that James left the telegraphists’ radio room once more to deliver a message to the bridge.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn his way there, he would have heard the German 12” armour-piercing shells roar in to strike the ship and felt the vibrations rippling through the deck.

On the bridge, an officer handed him another message for immediate transmission. As he returned to his post, James found that the entire main radio room was gone. One of Derfflinger’s shells had hit it, killing all nine of his shipmates. James said later, “I don’t remember being in the least bit frightened, I was just doing the job I was trained to do.”

Despite the damage and casualties, Barham’s 15” guns and fire control systems were untouched so she continued the fight, managing to rejoin 5th BS and Jellicoe’s main fleet that evening. Barham eventually survived the battle albeit with the loss of four officers and 23 men killed.

Overall, the British Grand Fleet lost 6,097 men and 14 ships. Although the Germans lost 2,551 men and 11 ships, they were quick to declare a great tactical victory. Jellicoe on the other hand remained silent. No communications were issued until the Grand Fleet returned home which allowed the government and the public to assume from the German’s statements that the British navy had, at best, slunk away or at worst, been defeated.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn fact the result was that the German High Seas Fleet never came out of port again to confront the British who, emboldened, reinstated their naval siege, tightening the blockade of German ports and intercepting supplies to their armies in the field and their citizens.

Barham returned to dock for repairs and rejoined the fleet that autumn. Two further post-war refits followed and she returned to active service in the Second World War before being destroyed by three torpedoes in 1941.

James returned home to Preston when the war ended in 1919. He ‘ran away’ a second time in early 1922 when he eloped with his fiancée Edna, to marry at Preston Register Office. They moved to Fulwood and James began work as a financial clerk in offices off Fishergate. Together they raised a son, Jim, and daughter Joan.

Jim, now 86, recalls his father as a quiet, religious man but also someone who enjoyed parties with friends and family.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “My dad never talked about the war much at all. He did say though how the loss of his friends when a shell hit the signals room affected him and that was the reason he never missed an Armistice Day parade.”

At the outbreak of the Second World War James re-enlisted and was appointed a Special Constable. He put his own radio equipment and Morse code skills to use in his garden shed, listening in to German communications on behalf of the authorities attempting to identify troop movements and enemy spies. He died in 1993.

And were it not for his lucky escape from a German shell at Jutland, I would never have met and married his granddaughter.