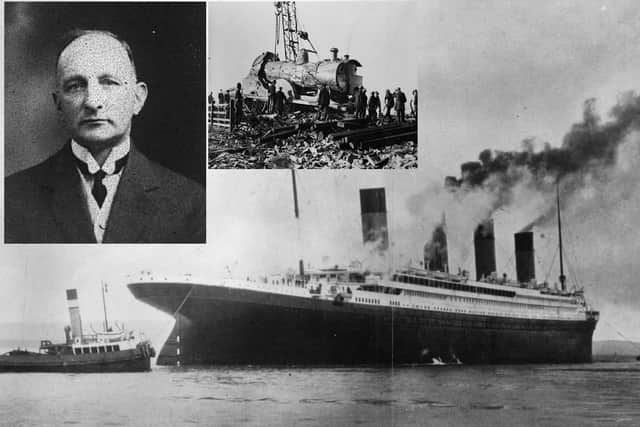

Final destination: The Blackpool man who missed the Titanic, survived another ship crash, and was killed by a train near Lytham

and live on Freeview channel 276

Yet it’s true. That was the remarkable life - and death - of Commander Charles Greame.

Born in Blackpool on October 5, 1874, he was the fifth of eight children of the founding father of The Gazette, Alderman John Grime.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe black sheep of the family, he eschewed its extensive newspaper holdings and, determined to make his own way in the world, changed his name.

After marrying Muriel Taylor in 1902, Charles settled permanently in the heart of the resort, in Lincoln Road, although his passion for the sea would take him around the world.

Having acquired his Master's Certificate, apart from service with the Royal Navy during the Great War, his entire maritime career was spent with the White Star Line.

He was on a Mediterranean cruise as a serving officer when, in April 1912, he was ordered to travel over land to link up with the Titanic as it undertook its maiden voyage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut, due to unexpected delays, he only reached Cherbourg, the French destination of the liner's first stop-over, which lasted 90 minutes and let 281 passengers on, in time to see the ship sail into the distance on April 10.

Whether he felt relief or survivor's guilt, the sinking of the Titanic five days later in the North Atlantic Ocean, with more than 1,500 people killed, will surely have played on Charles' mind as he went on to work on White Star Line's prestigious routes, with ships under his command including The Zealandic and The Bardic.

Built in Belfast by Harland and Wolff in 1919, the 7,950 ton Bardic, with Charles in charge, arrived in Liverpool from Australia on July 6, 1924.

With the passengers disembarked, the ship and crew made their way to Plymouth to offload a cargo of wood, grain, frozen meat, and lead.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut, losing its way in deep fog, The Bardic struck a rock close to the Lizard Lighthouse, Cornwall, and was left stranded and badly damaged.

With the crash making headline news, Charles' distinguished career came to a sudden end.

For a second time, a ship had put him on his fateful path to disaster.

After attending an inquiry into the accident in Liverpool on November 3, 1924, Charles travelled home on the 4.40pm business express to Blackpool Central Station, where the Coral Island arcade now stands.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPassing through Preston on time, the train approached a curve at Warton about a mile-and-a-half from Lytham station, where it was due at 5.45pm.

Suddenly, the engine left the rails and ploughed into a signal box, almost demolishing it.

The four coaches, full of mill workers, office girls and businessmen, were dragged to disaster, the first two toppling over and the rear coach bursting into flames.

Passengers were flung across the coaches and a horrific scene unfolded in the gathering darkness with a twisted mass of metal and wood all around.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe cries of the injured filled the evening air and the only light was from the flames engulfing the rear coach as the survivors attempted to escape from the tangled wreck.

The engine itself ended up some distance down the line with the driver and stoker being thrown out.

The driver, William Crooks, who had struggled to halt the train, was killed as it ground to a halt but the stoker, Frank Livingstone, was more fortunate, being flung from the wreck and landing safely except for a bruise or two.

Likewise signalman William Hornby, who was manning the signal box, was flung into a field and suffered a head wound.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPassengers in the rearmost carriage who had suffered only bruises had the foresight to hurry down the line and warn an oncoming express of the disaster ahead.

Other travellers whose injuries were not severe began the work of liberating the less fortunate trapped by timber and metal.

Ten minutes after the collision a motorcyclist who had witnessed the crash informed the staff at Lytham station and soon there were plenty of medical people and willing helpers at the scene. Flares were lit and huge bonfires illuminated the gruesome spectacle.

Those in need of urgent medical treatment were dispatched to the Lytham Cottage Hospital, but it was close to midnight before all possible aid had been given.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnly the bodies of those crushed to death beneath the wreck remained for removal.

The final death toll was 14 and included Charles, who, despite being initially trapped under the train, had bravely attempted to rescue others before being taken to the hospital, where he succumbed to his injuries.

Also mourned were three women from a mill at Kirkham who had only been on the train a matter of minutes.

Although another 12 people needed lengthy hospital treatment the feeling was that many had been fortunate to escape relatively unscathed from the ordeal

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn inquiry held within days concluded a wheel, discovered in a nearby field, had a flaw beneath the surface and caused the express to derail.

Both the signalman and the stoker of the engine told how they had seen sparks flying from the engine’s wheels just prior to the accident.

A verdict of accidental death was recorded in each instance when the inquests were concluded.

After being re-floated and repaired, The Bardic, renamed The Marathon, ended up being sunk by German battleship Scharnhorst in the Atlantic Ocean northwest of Cape Verde on March 9, 1941, with its crew taken as prisoners of war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThose who did die aboard the Titanic included young crew member Leonard Taylor, of Sherbourne Road, North Shore, a Turkish baths attendant, who helped women and children onto the lifeboats.

Charles Sedgwick, an engineer for the council's electricity department, also died. He was travelling second class without his new wife Adelaide, who had refused to go.

It is believed the wife of a third passenger from the Fylde coast, Arthur Gee, had begged her husband not to sail for fear of an impending disaster.

The father-of-four, of Riley Avenue, St Annes, was on an important business trip, and helped engine room crew desperately trying to keep the ship afloat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is thanks to our loyal readers that we can continue to provide the trusted news, analysis and insight that matters to you. For unlimited access to our unrivalled local reporting, you can take out a subscription here and help support the work of our dedicated team of reporters.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.