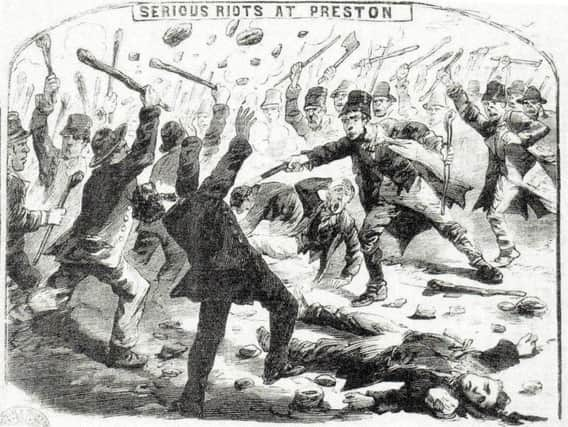

Rioters on Preston's streets

It is fair to say that 150 years ago, with the Whitsuntide processions well established in Preston, there was a keen rivalry between the Roman Catholics, Protestants and Orangemen who paraded

annually along streets.

The Whit Monday marches were attended by many local folk, along with a great influx of visitors from across Lancashire, many of whom arrived by train.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1868 from morning until night the streets were thronged with people, many of whom were decorated with ribbons and rosettes of almost every hue. Imposing parades were made by the Church of England Sunday Schools, the Catholic Guilds, and the Order of Orangemen.

The Church of England had more than 8,000 walkers, the Catholics upwards of 3,000 and the Orangemen numbered more than 600. It was anticipated some trouble might have arisen during the Orange parade, but this did not materialise.

However, two of the school processions in connection with the Church of England were interrupted by boisterous Irishmen. One of them being brought before the magistrates and being fined for his behaviour.

The Orchard area, which in those days was an uncultivated patch of land, was something of a gathering point with a makeshift fairground for those participating or simply observing the day’s events.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to the Preston Herald, ‘It was occupied by a nondescript variety of vendors of crotchets and quavers, theatres of the shanty style, obstreperous auctioneers, swing boats, hobby horses and a heterogeneous heap of other characters and articles.’ Alas the fun, friendship and frivolity was not to last as events of later in the week would put Preston in the national spotlight. Events in the Moor Lane area around the Craggs Mill windmill, known locally as ‘Paddy’s Rookery’, on account of the number of Irish folk settled there, turned violent on the Tuesday evening.

Two lads wearing orange and blue ribbons in their hats were passing along Milton Street when a party of Irishmen set upon them. This led to a gentle rebuke from a man passing along the street who in turn was viciously attacked.

A crowd immediately gathered and a number of Englishmen proceeded to defend the stricken man. A cry was quickly spread, and the Irish appeared from all quarters; stones were uprooted from the pavement and thrown, many people were injured – although not seriously – and a number of women were spotted providing their party with brickbats and other weapons.

The crowd was eventually dispersed, but there were fears of more violence. On the Wednesday evening as two men, both Roman Catholics, were passing along Milton Street, shots appeared to be fired at them from one of the houses. The pair were rushed to a house in a neighbouring street in a bloodied state. The announcement of this excited the wrath of many and by 9pm the street was crowded with opposing factions of Irishmen, who were attacking their foes with stones.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe police, led by Inspector Cunningham, arrived on the scene quickly, but when they got there all seemed relatively quiet, although crowds of people populated the neighbourhood.

A number of constables then began dispersing the crowds, helped by a local priest Father de Betham who urged the Catholics to go home. Meanwhile, one of the injured men, called Robert Alston, had been taken to the Spinners’ Arms on Lancaster Road, bleeding profusely and in a fragile state. A doctor found eight wounds on the man’s head and face and identified them as cuts and abrasions, not gunshot wounds.

On the Thursday afternoon men were seen parading the neighbourhood, wearing ribbons of red and green, and the shopkeepers put up their shutters early. When evening drew near people flocked from all parts of the town full of curiosity.

The Irishmen mustered in force, with no fewer than 2,000 gathered. When the police arrived they were greeted with yells and hisses, but after a determined effort managed to disperse them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAll was quiet for the rest of the week and news that Alston was on the road to recovery had, no doubt, helped to quell the fury of those keen to take revenge. Wanting to ensure there were no more public disturbances, the Mayor of Preston, Miles Myres (pictured inset), issued a proclamation stating any intimidation, violence and unlawful assemblies would lead to prosecutions.

Press reports nationwide had suggested Preston was a ‘hot bed of rioting’, but the severity of the clashes was played down locally, although the ‘Illustrated Police News’, proud of the way Preston police had dealt with the matter, published a sketch in their next issue of a rioting mob in the town.

The Preston Herald accused the Preston Chronicle, in particularly their editor Anthony Hewitson, of overelaborating his account, with the following paragraph being criticised: ‘A tremendous fight ensued. Stones were torn up from the streets; pokers and sticks were seized with a vengeance; there was a wild flinging and flying of the forces of Orangeism and Catholicism; cursing men, screaming women, and crying children were running about; shutters were run up and pushed in for fear of breakages; eventually blows were given, men fell, blood flowed; and, for a considerable time, there was a wild fandango of fury as was ever bred by the genius of fanaticism.’

Happily, the events of 150 years ago did not diminish the enthusiasm of the Whit Monday parades. In fact, they got bigger and more spectacular as the years passed and gave such pleasure and pride to later generations of Preston folk, only being halted when the Second World War arrived. In the years that followed, attempts were made to re-establish them with church, youth, faith and loyal Orange parades taking place sporadically.