A Prison Through Time - what life's like in Preston Jail

There is one place in Preston where the people within are familiar with the phrase ‘lockdown’ unlike the majority of the city’s residents.

Standing as it does on Ribbleton Lane the HMP Preston complex was opened in 1789 and was named the House of Correction. It was the brainchild of the celebrated philanthropist and prison reformer John Howard. Howard travelled the world studying different forms of punishment and the Preston project was to be among his last before his death in 1790.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe House of Correction was where thieves, beggars and other petty criminals would be put to hard labour in an attempt to reform their criminal tendencies. Most of the inmates would not be in for a period any longer than two years, with the aim to reform inmates as well as punish them for the wrongs they had done.

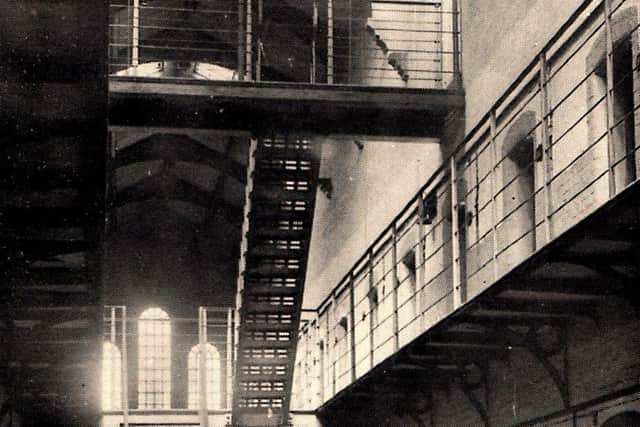

The buildings for reception of criminals were surrounded by a three tier high boundary wall with a governor’s residence, large sessions house, wings containing ground and attic cells, weaving shops, a hospital and a chapel. It was an impressive complex at the time and down the decades extra wings were added with additional cells. Generally when the prison inspectors visited they wrote favourably about the prison.

By 1819 the prison was being governed by William Liddell who had two turnkeys and two taskmasters under him. Together the five had to control 350 prisoners who were mainly employed weaving and cotton picking, the goods produced being sold to Horrockses.

Work began each day at 6am and continued until dark, or 7pm during summer. Two prisoners shared a cell furnished with straw mattresses and bed boards. The prisoners diet consisting of bread, potatoes, oatmeal, cheese and stew. Any prisoner attempting to escape would be shackled in irons and most petty offences committed in the gaol led to the loss of a meal.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe new structure had replaced an earlier House of Correction which stood to the west of Friargate and opened in 1619. John Howard had visited that place in 1777 and described it as a dreadful, dirty and dilapidated prison.

In 1832 the new prison had four Martello towers built to protect the prison from threatened attacks by mobs of machinery breaking hooligans, while two years later the governor’s residence was reconstructed into the castellated form which still exists today – that building being used as the Stanley Street police station in more recent times.

When historian Anthony Hewitson wrote about the prison, almost a century after its opening, he stated that there was accommodation for up to 500 prisoners and that in 1883 the population was 70 females and 274 males.

The male prisoners being put to stone breaking and mat making, while the women were occupied with washing, knitting, needlework and wool picking. The prisoners generally earning a shilling a day and reckoned to cost the taxpayer £17 a year to be confined. The prison governor at the time was James King who had been in charge for almost 20 years. In 1878 the prison responsibility being transferred from the county magistrates to the Government.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHewitson also recalled the role the Rev John Clay the former prison chaplain, who died in 1858, had played in the prisoners’ welfare having made great studies of crimes and criminals and attempted to lead the prisoners on the way to rehabilitation.

The 19th century Preston Prison was a foreboding place and there are many a tale of escape attempts and murderous activity within its walls. There was the Sunday in July 1837 when eight prisoners fled from the House of Correction during visiting time, with those eventually apprehended being transported across the seas for seven years. In the year 1848, a young man named Thomas Dewhurst, in prison for pigeon stealing, scaled the prison wall and went on the run. Committing burglaries as he went he was eventually caught and transported for seven years. In 1852 Richard Whitty made an unsuccessful attempt to free his brother William from the gaol.

In January 1858 there was pandemonium in Preston Gaol when Thomas Kershaw, awaiting trial for the murder of his father, attacked Charles Collins another inmate with a shovel. He was subsequently declared insane and detained during Her Majesty’s Pleasure.

The Preston Gaol was clearly in demand in the early 20th century as a report of 1913 revealed. At that time the prison population was 4,038 including 676 females and this was a decrease of 313 prisoners from the previous year. The authorities were claiming better education of convicts was beginning to pay dividends.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSadly, cases of suicide were all too frequent with prisoners going to great lengths to end their days behind bars. In May 1901 thief George Berry ended his life by drinking a tin cup of carbolacene that contained the drippings from a cask of the liquid cleaning agent.

In April 1906 William Cook, a prisoner from Blackburn, was found hanged in his cell after making a noose from cleaning rags he had collected. Perhaps, the suicide in 1922 by hanging of George Whittaker, a bricklayer from Burnley, summed up the plight of the prisoners. In a message written on a slate he said – ‘I am fed up with this life, so I am going to see what the next is like.’

Major Augustus Benke, who was the Governor of Preston Gaol in the 1920s, claimed his intention was to return the criminals to society as better people. Under his command the prisoners woke at 6am and after washing and dressing had an hour of physical drill. Their working day was from 9am until 6pm with a break for a midday meal. The meal eaten in their cells included soup, meat and fresh vegetables. The work undertaken by the prisoners included the manufacture of thousands of pairs of clogs, hammocks for the Admiralty and mailbags for the GPO.

In November 1925 it was announced that the female section of Preston Gaol was about to close in consequence of the small number of women serving time there. There had been a gradually decline in the number of women inmates partly due to changes to the Probation Act and those still incarcerated were shipped out to Liverpool, Manchester and Durham. Also that month Major Benke departed to take over as the Governor of Pentonville Prison and Mr L C Ball took over at Preston.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt that time the number of male prisoners averaged around 1,400, of which 1,000 were convicted felons and 400 were debtors. As the April 1931 Preston County Sessions ended Judge Openshaw invited the Grand Jury on the traditional tour of Preston Jail, telling them they would be the last to do so as the prison was about to close. Jail capacity elsewhere in the county being sufficient to accommodate those in Preston Jail.

The prison remained closed for the next seven years before Preston Corporation became the owners of Preston Prison in July 1938. The intention was to demolish the grim pile and clear the area for development. A reporter from the Lancashire Evening Post visited the place that week and concluded the abandoned premises fairly gave him the creeps. He described the buildings as musty and forlorn and peopled by ghosts – the pitiful, repellent ghosts of lost hope, frustration, callous self will, thoughtlessness, intemperance and all the other human frailties that land a man or woman behind prison bars.

The huge blocks of cells were populated only with decay, neglect and emptiness. The prison chapel was bereft of all except its rows of dust laden pews where once the convicts prayed for redemption. The hospital, the lecture room, the laundry, kitchen and workshops all had an eerie stillness about them and the exercise yard once populated daily by prisoners grateful for a breath of fresh air was overgrown with tall weeds.

However, any plans to demolish Preston Prison were put on hold as the Second World War arrived. Initially it became a Civil Defence store and by September 1942 it had became a Royal Navy detention centre. A role it would fill until January 1947 housing more than 9,000 naval offenders during that period.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe future of Preston Jail was in the balance until March 1948 when it was announced it would reopen again as a civilian prison. The Prison Commissioners taking over the premises as a surge in crime had filled other prisons in the area.

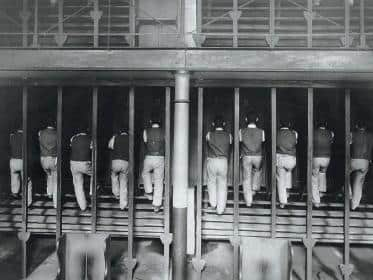

Thirty years later in 1978 the prison was the residence of 574 male convicts under the watchful eye of Governor Albert Greasley. Inmates were spending 12 hours a day locked in their cells, some measuring only 6ft wide and 12ft long, six hours working on tedious production lines and an hour a day walking in circles around the exercise yard. The food budget was £3.60p per inmate per week and the kitchen staff served up a daily menu that included porridge or boiled egg for breakfast, soup and cheese flan for lunch, lamb cutlet or cottage pie for tea and fruit loaf for supper.

The inmates were a mixture of petty thieves, burglars, swindlers and murderers, including lifers, all thought suitable for this Category C prison. One prisoner’s view of life behind bars was that it was ‘dead strict and incredibly boring’.

Unrest in prisons nationwide in April 1986 led to a wave of rioting in jails. Preston eventually got caught up in the riots with 400 inmates of the prison battling with prison guards in an attempt to take over. A roof top protest was part of the disturbance, but the prison officials held their ground and quelled the rioters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy 1990 it was classified as a local prison and by 1996 a long needed refurbishment was underway with prisoners ‘slopping out’ for the last time. Prisoners were moving from the prison’s old C wing to A wing where the cells were fitted with their own toilets at a cost to the taxpayer of £2.2m. The population at that time was 310 rising to 450 when including those awaiting trial or transfer to a training prison. With all the wings having their own shower blocks the central bath house was about to be demolished.