Lost story of the first black soldiers to serve in Lancashire

In the 18th century the fashion for exotic ‘Turkish music’ and belief in the ‘natural propensity of black people for music’ resulted in black men being enlisted to serve as military musicians in British Army regiments.

Playing percussion instruments such as cymbals, tambourines, big drums and kettle drums, they were employed as symbols of regimental prestige.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdInitially enlisted by only higher status regiments, by the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815), most regiments had some black presence, be it individuals or small groups of drummers, trumpeters or bandsmen.

In addition there were black wives, girlfriends and children, for example Mary Seacole, who was the daughter of a Scottish soldier and Jamaican healer, and whose service as a nurse in the Crimea War saw her voted the nation’s voted greatest black Briton in 2004.

The British Army of the 18th and 19th centuries made no distinction between people of African or Asian origin – simply referring to them as being ‘black’ or ‘of colour’.

Some men were recruited while the Army served in the Americas, Caribbean and India, however, most of were recruited from the black population resident in Britain and Ireland, while a number were recruited from among French Prisoners of War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhilst stationed at home in Britain and Ireland, the role of a black military musician may well have been to promote regimental prestige. However, on campaign their role was to communicate orders in battle. With shot and shell making verbal orders difficult to hear, commands were relayed by the beat of a drum or the call of a trumpet.

Many black soldiers served as bandsmen, whose secondary roles were to act as medics or serve in the ranks. In several regiments black soldiers were employed at company and troop level (in the infantry and cavalry respectively), and these battlefield communicators required quick wits and situational awareness to fulfil their role.

Thus, black soldiers were not simply bandstand or parade ground eye-candy. They served with their regiments during the American Revolution, the Peninsular War and various small wars as Britain expanded its empire – including in Africa, India and the first Afghan War.

While the War Office purchased thousands of African slaves for the West India Regiment in the 1790s, and some army officers owned slaves, there is no evidence that individual British regiments purchased slaves. Instead, it is likely the existing black population of Britain was large and willing enough to meet the demands of recruiters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe few soldiers for whom anything of their previous lives are known appear to have been free, or free when enlisting. Black recruits who enlisted in England came from Africa, India, North and South America and the Caribbean. Most enlisted in ports such as London, Bristol, Liverpool and Plymouth.

The British Army of the period was arguably the finest in the world, however, it was plagued by drunkenness and violence. It was the Duke of Wellington himself who referred to it as “the scum of the earth”, and so the decision by so many black men to voluntarily enlist does beg the question as to how bad was civilian life was?

Discipline was enforced by flogging. Drummers and trumpeters were responsible for flogging, and this inverting of the racial hierarchy made black soldiers unpopular on occasion.

Black soldiers were restricted to musical roles and few were ever promoted to non-commissioned officer rank – those that were invariably being experienced combat veterans.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA number were racially abused by both white civilians and soldiers, and one was the victim of a racially motivated murder by soldiers of another regiment. Yet, re-enlistment rates among black soldiers were higher than their white peers, and their service was highly praised.

Black recruits were also sought from among the black population resident in Lancashire: James Hacket, born in St Vincent in 1783, and described as ‘a man of colour’ enlisted in the Scots Guards in Liverpool in 1800. He died in the Peninsula Campaign in 1811.

Thomas Clarke, an African servant born in 1797 was recruited in Liverpool by the 88th (Connaught Rangers) Regiment of Foot in 1820. Military service also brought black soldiers to Lancashire. Loveless Overton, born in Barbados in 1780 and Archibald Robertson, born in Grenada in 1777 and described as ‘a mulatto’, were both serving with the Ayrshire Fencibles in Manchester when they transferred to the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards in 1800.

Jeremiah Salisbury, a black trumpeter in the 4th Dragoons died while stationed in Manchester in 1787. Black soldiers served in the antecedent regiments of the modern regiments connected to Lancashire: The Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment and the King’s Royal Hussars:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCharles Dupree, born in St Eustia in the West Indies c.1775 served with the 30th (East Lancashire) Foot between 1802 and 1827, most of his service being in India.

Prior to joining the 30th Dupree had served in the Royal Irish Fencibles and the Northamptonshire Militia. He died in Malta in the late 1820s.

The 40th (South Lancashire) Foot had at least two black soldiers: Firstly, Perry Brookings, born in Barbados c.1791, who served as a drummer between 1815 and 1833.

He had previously served in the Royal Navy. Secondly, William Rind, described as ‘a half-caste East Indian’ born in Stirling, Scotland c.1796. Rind served as a boy soldier during the Peninsular, prior to re-enlisting in the 40th Foot in 1818 and serving until 1841. He was transported to Australia for the ‘crime’ of homosexuality in 1846 and died in Hobart, Tasmania, in 1857.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe 14th Light Dragoons had several black soldiers serving as trumpeters and in the band, including Henry Anthony, born in Africa c.1773 and who served between 1802 and 1814. Anthony, a married man, died in London in 1854.

The 20th Light Dragoons also employed black soldiers, many of whom had been recruited while it served in the West Indies in the 1790s. However, unlike most regiments it promoted several to the senior non-commissioned officer post of Trumpet-Major. Including Robert Yates, born in St Domingo c.1782, who served with the 20th from 1798 to 1818.

A married man with a family, he saw action in the Peninsular campaign. The 20th Light Dragoons also enlisted a black Lancastrian: William Barnes, born in Liverpool c.1795, enlisted in the regiment in Sicily in 1814. (It is possible that he arrived on the island as a sailor).

He was recruited by Trumpet-Major George Tombs, a black soldier born in St Domingo. Barnes was discharged from the regiment in Cork, Ireland in 1817. Meanwhile, Tombs served as Trumpet-Major Sergeant in both the 20th Dragoons (1798-1818) and the 2nd Dragoon Guards (1819-1822).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe presence of black soldiers was not restricted to the regular regiments of the British Army. Locally raised militia units, such as the Royal Lancashire Militia (RLM) also enlisted Black recruits to serve as bandsman.

In 1808 two men were recruited by the RLM from among the French Prisoners of War held in Portsmouth: Louis Dejane, a soldier born in Guadeloupe c.1784, who had been captured at sea in 1806, and Pierre Nicolle, born c.1786, who was a black servant on board the French Frigate Le President when it was capture by HMS Canopus south of the Scilly Isles in June 1806.

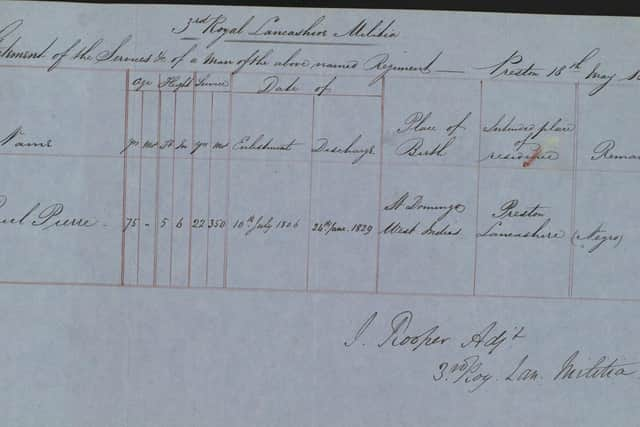

They appear to have been the replacements for John Battis, born St Domingo c.1781, who, in 1808 had left 3rd RLM after two years-service to enlist in the 58th (Rutlandshire) Foot.

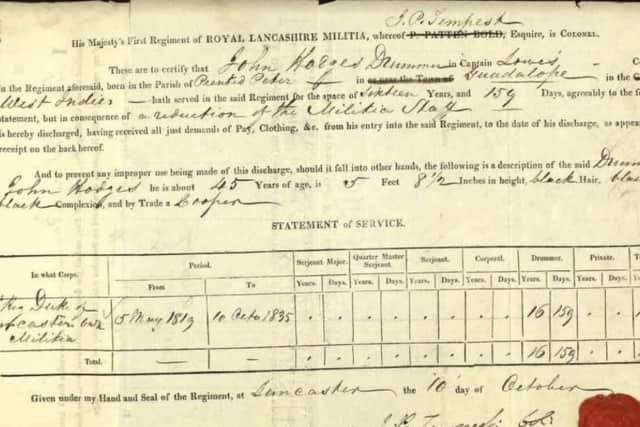

The names of French POWs were usually anglicised when they enlisted in British regiments, and ages were approximate. It is entirely possible that Louis Dejean was John Hodges and Pierre Nicolle was Paul Pierre.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTwo of the Black soldiers who served on the permanent staff of the 3rd RLM in Preston qualified for an out-pension from the Royal Hospital Chelsea and subsequently settled in the town: John Hodges was born in Guadeloupe c.1790. He had reputedly been captured after serving with the French Navy at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805).

In 1815 he enlisted in the 1st RLM, later transferring to the 3rd RLM where he served as a drummer and a cymbalist in the band.

John Hodges was discharged on a pension in October 1835 due to ‘a reduction of the militia staff’. He settled in Preston, where he had spent much of his service, and lived and worked as a cooper (his occupation prior to enlistment) on Tithe Barn Street, (now Tithbarn Street next to bus station). John Hodges died in February 1837.

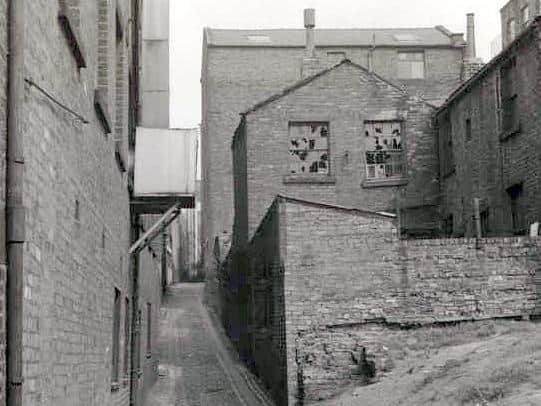

Paul Pierre was born in St Domingo c.1778. He enlisted in the 3rd RLM in 1806 and served until June 1829. Paul and his wife Catherine, (believed to have been born in Ireland c.1789), had probably met while he served there with 3rd RLM between 1813 and 1815. In Preston, the family worshipped at St Wilfrid’s Catholic Church, and some of their children were baptised there: Mary Ann (1815-1824). Ann (1820-). Esther (1822-1891). Marianne (1823-1861). Maria Olivia (1829-). Frances (1838-). Mary (1840-1841). In 1841 the family were resident at an address at the back of Old Cock’s Yard in Preston. Catherine died in 1843.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1851 Paul Pierre was living with his daughter Frances and her husband John Aspinwall, a linen draper, in Harrington Street, Preston. Also residing with them were Catherine, the three-year old daughter of Frances and John, and Francis Paul Pierre, the 13-year old nephew of Frances (and grandson of Paul).

Life must have been difficult for Paul Pierre, because in 1853 he applied to the Army for a pension for his service in the RLM, giving his place of residence as Preston. His application – which identified him as a ‘negro’ - was successful. Pierre died of debility in Preston in April 1855. Today he has descendants in Preston and in the USA.

* John D Ellis is an historian and educator.